Why not redshirt the boys?

Some good-ish arguments against my idea, which I don't find convincing

Top line: By default we should start boys in school a year later than girls, to account for the different rates of brain development by sex. That’s what I argue in my new Atlantic piece, “Redshirt the Boys”. I’ve had a bunch of responses, good and bad, and some serious criticisms that I want to address here. (I say more about all of this in my book, Of Boys and Men).

Stat of the week: The level of impulse control of the average 10-year old girl is only attained at by the average man by the age of 25.

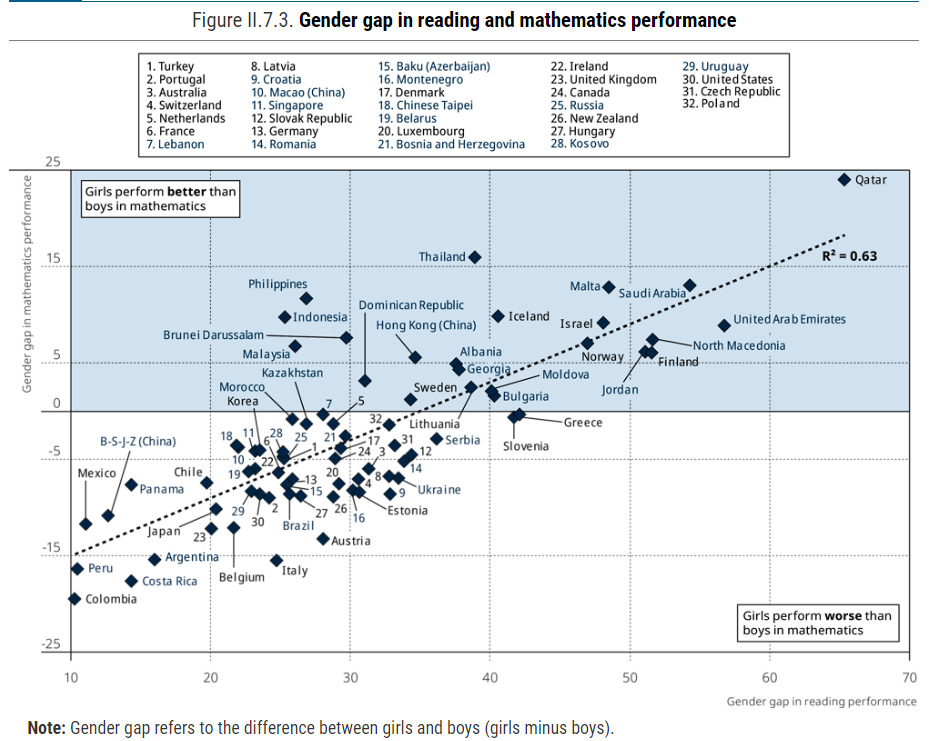

Chart of the week:

Why it matters: We have some big education gaps by gender. In part these can be explained by biological differences in the timing of brain development. These differences should be taken into account in education policy, if we’re serious about equity.

First let me say a huge thanks to those of you who have subscribed to Of Boys and Men, and helped to spread the word. There’s a lot of you. Here’s an easy way to share:

So, here’s what I wrote in The Atlantic:

I believe the biggest reason for boys’ classroom struggles is simply that male brains develop more slowly than female brains—or at least those parts of the brain that enable success in the classroom. The gaps in brain development are clearly visible around the age of 5, and they persist through elementary and middle school. (As Margaret Mead wrote of a classroom of middle schoolers: “You’d think you were in a group of very young women and little boys.”)

The brain-development trajectories of boys and girls diverge further, and most dramatically, as adolescence progresses—with the widest gaps around the age of 16 or 17. I hardly need to say that these are crucial years for educational achievement…

By far the biggest sex difference is not in how female and male brains develop, but when. The relationship between chronological age and developmental age is different for girls and boys. From a strictly neuroscientific perspective, the education system is tilted in favor of girls.

A key point here is that the boys who would benefit most from a delayed start, those from less advantaged backgrounds, are currently the ones least likely to get it: I dig into these numbers in a related Brookings post, “Who redshirts?” At one well-known East Coast private school, who shared their data with me, almost one in three (30 percent) of their graduating senior boys were born before October 2003, the formal cut-off date for school entry for that year, compared to seven percent of the girls.

On twitter and over email I’ve encountered some serious arguments made against the redshirting proposal. I take these seriously, and have given some responses here. One thing’s worth saying up front. As I stress in the book, any move to enact the proposal should initially be on a pilot basis, with careful evaluation built in.

Objection 1: Boys aren’t really behind in education

My friend Jonathan Rothwell (who has his own substack here) countered the claim that boys are that far behind girls. Here’s one of his sallies:

On many measures of educational success in this country and around the world, boys are doing as well or better than girls, though usually not on reading. PISA (15-yr olds) on math & science. U.S. NAEP (grade 9 or 12) results on math & science.

He adds that “cognitive data on adults in PIAAC are more in favor of men”.

This is a big objection. And Rothwell’s not alone in making it. If boys aren’t really behind at all, why are we even having this conversation? Here’s some rejoinders.

Even on the measures Rothwell points to, overall, boys are behind. In the NAEP, there’s now no real gender gap on math and science (where girls have caught up to boys), but a big one in English. You can check out all the scores using this handy NAEP explorer. The bottom line is that by 12th grade, there is a 3-point gap in favor of boys in both science and math - but a 13-point gap in favor of girls in reading.

The NAEP are tests of ability in these subjects, closer to capturing cognitive skills. But that’s not where boys lag girls. The big difference, as I say in the Atlantic, is in non-cognitive skills:

The problem of self-regulation is much more severe for boys than for girls. Flooded with testosterone, which drives up dopamine activity, teenage boys are more inclined to take risks and seek short-term rewards than girls are. Meanwhile, the parts of the brain associated with impulse control, planning, and future orientation are mostly in the prefrontal cortex—the so-called CEO of the brain—which matures about two years later in boys than in girls.

And: literacy is much more consequential for later educational attainment than math or science (see here and here). So in terms of college-going especially, the skill that likely matters most is the only one where there’s a gender gap - and it’s in favor of girls.

Colleges do not admit students based on NAEP scores! Nor should they. As Dylan Conger writes in the Annals: “High school grades also matter much more than standardized reading and math exams in high school.“ And as I showed last week, there’s a big gender gap in high school GPA.

The international story on PISA is similar: big gaps in favor of girls in reading, very much smaller gaps in favor of boys in math and science, and with wide variation across countries:

A denial of the large gender gap in education in favor of girls, especially in advanced economies, simply does not survive contact with the data.

Objection 2: It’ll be bad for girls

A few folks worry what it will mean for girls to be in classes with older boys. Here’s a representative tweet:

And when we suddenly have boys physically dwarfing girls in high school even more because they’re a year older, will you write a think piece about how women need to be protected from physical intimidation by starting a year later?

I think in general these concerns are misplaced. If anything, I’d say having more mature boys in the classroom is likely to be be good for girls. This is consistent with the evidence for modest spillover effects from redshirted kids to their fellow classmates.

In terms of revealed preferences, it may be that girls actually prefer to be around boys who are older in chronological terms, and therefore more likely to be peers in terms of maturity. One data point is that 10th grade girls are almost twice as likely to be dating a boy from a higher grade (16.3%) as from her own grade (9.1%).

Objection 3: You’re blaming the boys

One reaction was that in pointing to these differences in biology, I am essentially blaming boys and men themselves for their educational underperformance. One tweet read:

“Rather than modifying schools to be a healthier environment for young people, it's advocating a hope you can sand off all the edges by delaying them a year. Of course it's only boys.”

And:

“Misandry masquerading as care and structural support. "The structure needs to change to adapt to males being developmentally inferior."

Another way to go would be to change schools so they work better for boys. This author treats the boys like they're the problem, as if boys needed another year of pre-K so they could be more like girls. Yuck

This surprised me, to be honest. I think it’s exactly the opposite: these are biological facts, over which no individual has any control. And I devote a whole chapter of my book to criticizing the way in which many aspects of masculinity have been pathologized as “toxic”.

But this is an important lesson learned. I now realize that I need to be more careful in how I frame the argument. In pointing to these biological differences, I clearly run the risk of doing precisely what I’m urging everyone not to do: to pathologize boys or men, by implying there’s something intrinsically wrong with them. In hindsight perhaps I should have anticipated that danger.

That said, I strongly agree that there is also very much more to do to make schools male-friendly: redshirting is far from my only proposal. I also advocate a massive recruitment drive of male teachers in K-12 (currently at 24% share and falling), and much greater investment in vocational training, which disproportionately helps boys and men. (See Chapter 10 of the book.)

I should say that there are some other challenges posed by my idea, not least in terms of phasing it in, legal arguments, how far the gender distributions overlap (which I’m doing some more work on), etc. But for now I’ll stop here. I really appreciate all those who read and commented on the Atlantic piece, and also those who have ordered and shared news about both the article and my book. Let me know what you think of all or any of this!

Lastly, as evidence that there are no new ideas in the world, it turns out that the proposal to start boys a year later was made by Dr Leonard Sax, in a paper for the American Psychological Association back in 2001. Sax is also author of the book Boys Adrift: The Five Factors Driving the Growing Epidemic of Unmotivated Boys and Underachieving Young Men.

ps. I haven’t forgotten that I promised last week to get into the whole issue of how to help more men into HEAL jobs (health, education, administration and literacy). That’ll be coming next week (I think!).

Be well -

Do young boys need to be redshirted or do they (and young girls) need for their fathers to take a red shirt?

Taking a redshirt as a father doesn't mean playing for the Bucs for one more year, in case you're wondering.

It means taking one year per child as primarily responsible parent. This time period roughly matches the time when women are primarily responsible parents during late pregnancy, delivery, lactation.

I am wondering if these educational delays in boys have to do with fathers not modeling that doing the grunt work is important?

Also, emotional availability in fathers is important for children to have emotional literacy about themselves, which provides motivation to learn and grow as well as the self control to focus in class and on homework?

So, why not advocate the fathers taking a redshirt to be primarily responsible parent (one year for each child) and to work on their emotional availability and literacy?

Why delay the boys to indulge bad daddery?

I’m never heard the term redshirt, but in Australia its pretty much the norm to start boys later than girls. It became a trend 20 years ago and has continued. Evidence suggests gains for boys in infants/primary but evens out by high school and then you’ve got adult males in high school; the smart ones (like my son) resent the extra year, and those that don’t want to be there cause trouble for everyone. Boys are concentrated at the top and bottom ends, there is a wide range of ability and social skills, whereas girls tend to concentrate around the average. I also don’t see what difference it makes if they’re going to be in early learning/pre-school anyway. Presumably they’d have to repeat kindergarten which seems unfair.