No, men’s views on policy haven’t really changed

So any gender gap in partisan preferences must have other roots

As the election draws near, there has been growing media attention to gender gaps in voting, especially among the young (See just this week’s coverage in The Hill, Axios, Vox, The New York Times, The New York Times and…The New York Times).

Some attribute this to a male backlash against women’s progress. But as we noted in a previous post, men’s support for gender equality does not appear to have weakened.

Others suggest that men’s views on policy may have shifted. Have they? As one way to answer this question, we looked at the American National Election Study (ANES) in February of this year, and compared it to results from a similar survey in 2022. (See Data Notes at the bottom of this post).

The bottom line is this: men do not differ significantly from women in the importance they attach to various policy issues; and their positions do not appear to have shifted much over the last two years. When it comes to concrete beliefs and policy preferences, then, the evidence for a dramatic shift among men seems thin. This suggests that any change in political preferences is being driven by other factors.

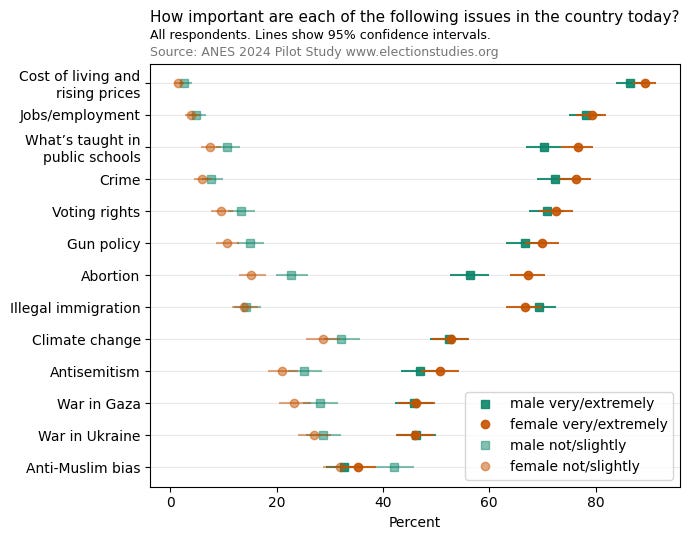

Men (mostly) care about the same issues as women

The ANES 2024 Pilot Study is a cross-sectional survey of approximately 1,500 individuals who completed the full questionnaire; the weighted sample is nationally representative.

The survey asks: "How important are each of the following issues in the country today?" on a five point scale:

Extremely important

Very important

Moderately important

Slightly important

Not at all important

We looked at the share of men and women who said a particular issue was “very” or “extremely” important compared to those who considered the issue “slightly” or “not at all” important.

Overall, the gender differences are slight and not statistically significant. Men tend to be stingier with their attention—they are less likely to say an issue is “very” or “extremely” important. But abortion is the only issue where this gap is statistically significant:

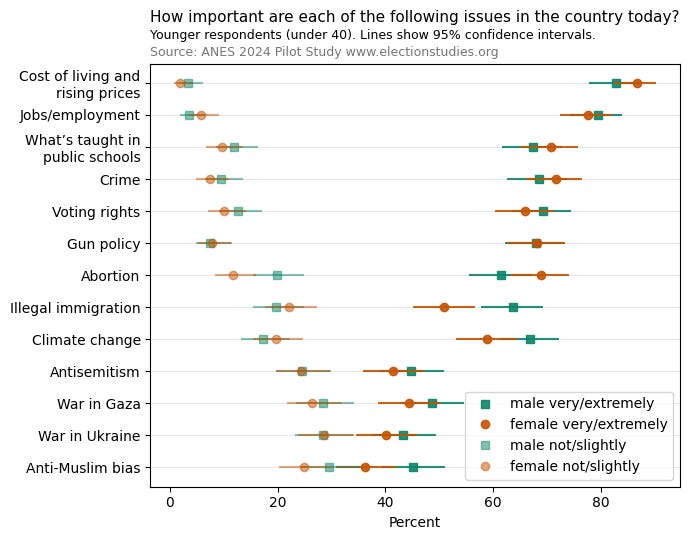

If we restrict our sample to men and women under 40, the gaps tend to be even smaller and again, abortion is the only issue on which men and women differ significantly:

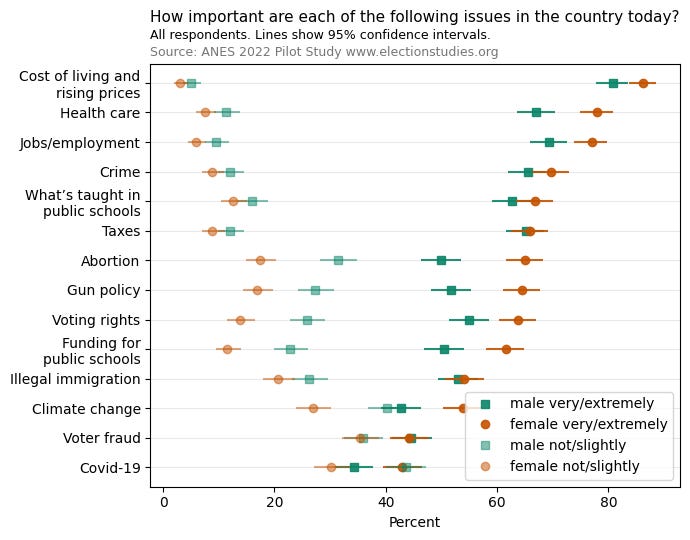

On policy, the gender gap is smaller than two years ago

If anything, the gap between men and women’s policy priorities has shrunk. Looking at the same set of questions in 2022, gender gaps in policy preferences were larger across a number of issues. Besides abortion, men were significantly less likely to consider health care, jobs/employment, gun policy, voting rights, public school funding and climate change to be “very” or “extremely” important:

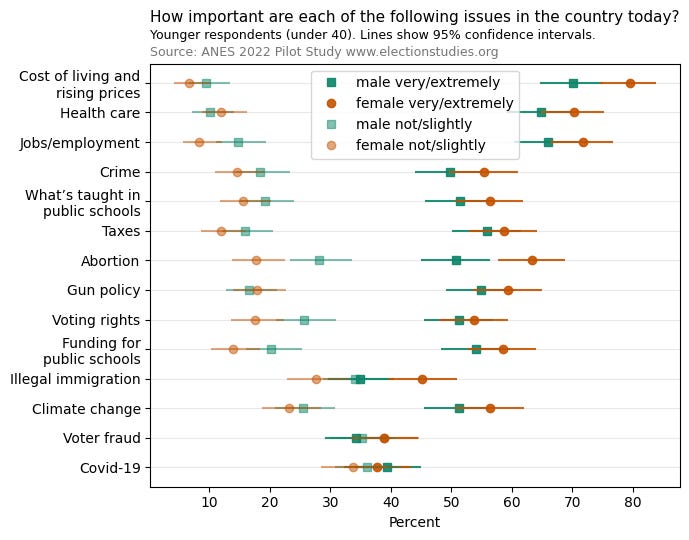

These gaps were smaller among younger men and women, and most are within the margin of error:

Men and women agree which party handles key issues better

One interpretation of these findings is that while men and women ascribe equal importance to an issue like voting rights, they might have different reasons for doing so. Women, for instance, might care because they find current laws too restrictive; men might care for the opposite reason.

If men and women both considered an issue to be equally important but differed substantially on why they believed this, we might expect to see some difference in which party—Republicans or Democrats—they believe would better handle the issue.

The 2024 survey asks, "Please tell us which political party— the Democrats or the Republicans—would do a better job handling each of the following issues, or is there no difference."

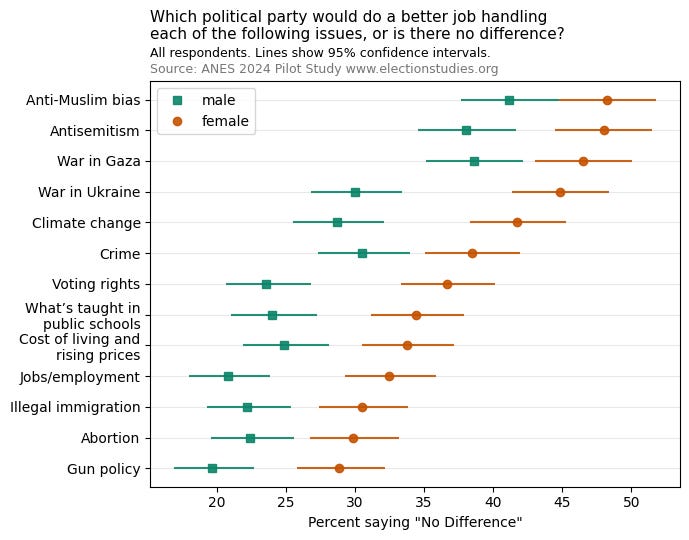

One gender divide that does emerge is that women are much more likely than men to say that there is "no difference" between the parties in terms of handling key issues:

On their face, this is a surprising result, given the perceived high engagement of women in this election. While more than 60% of women considered abortion an important issue, approximately 30% feel there’s "no difference" between the parties on this issue.

Potential explanations for this gender gap include:

Men are more likely to say that they are "very much interested in the political campaigns so far this year"—half of men compared to one-third of women—so they may be more aware of differences in the policies of the parties.

Even if they are not more aware, men may be more willing to express a preference, either from partisanship or a feeling that they should have a preference.

Some of the people choosing "No Difference" might be expressing dissatisfaction with the policies of both parties, rather than the belief that those policies are the same.

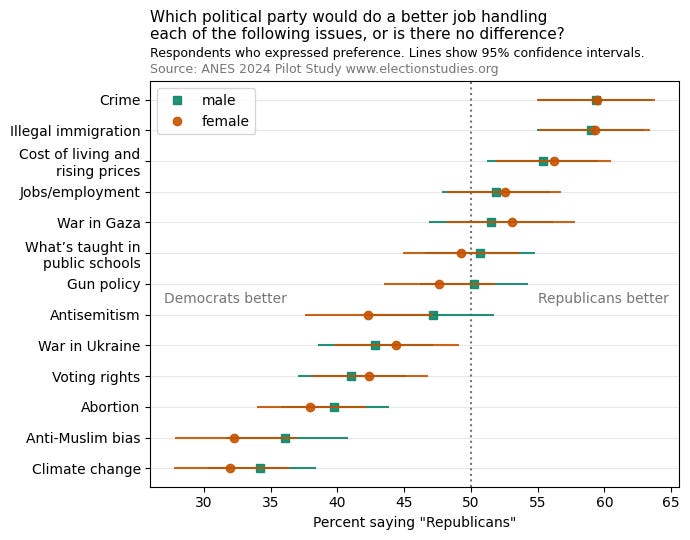

If we remove results from the respondents who said "No Difference" between the parties, and consider only those who expressed a preference, men and women are similar in their assessments of which parties are stronger on the various topics:

The majority of both men and women prefer Republicans on about half the issues and Democrats on the other. Looking at which are which, there aren’t any real surprises. As well, gender differences on all issues are within the margin of error and relatively small.

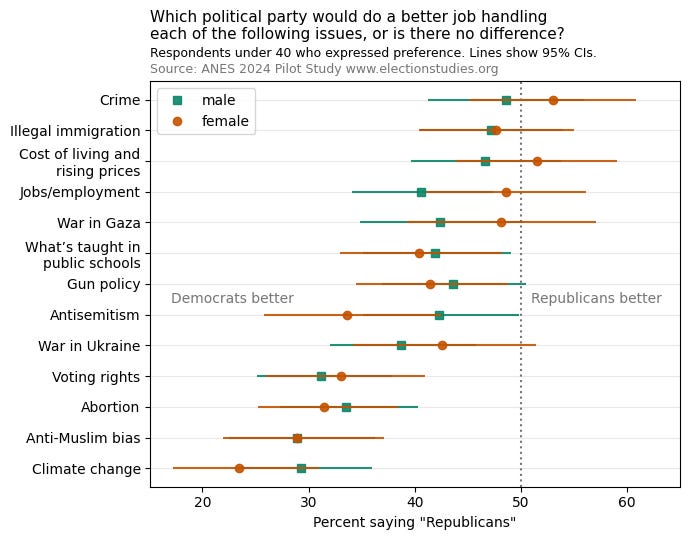

Here are the results for younger respondents.

Younger people lean more Democratic—in fact, there are only two issues where a majority of young women think the Republicans do a better job, and none where a majority of young men do. But the gender gaps are generally small, and all are within the margin of error (which is wider than the previous figure because the sample sizes are smaller).

The political gender gap resists easy explanation

We find scant support for the claim that shifts in view on policy are driving gender gaps in reported political preferences. Just as we found the claim of backlash among men toward the core principles of gender equality to be overstated, ANES surveys from 2022 and 2024 show persistently small and sometimes shrinking gaps between men and women in both their policy priorities and which party they believe would better handle them.

We see similar trends among younger voters too (though the sample sizes urge some caution here). Overall, it looks like men still care about the same things women do. There’s no easy answer to the question of why the political gender gap seems to be widening. But it does seem to lie more in the realm of culture than policy.

Data Sources

American National Election Studies. 2022. ANES 2022 Pilot Study [dataset and documentation]. December 14, 2022 version. www.electionstudies.org

American National Election Studies. 2024. ANES 2024 Pilot Study [dataset and documentation]. March 19, 2024 version. www.electionstudies.org

"The ANES 2022 Pilot Study is a cross-sectional survey conducted to test new questions under consideration for potential inclusion in the ANES 2024 Time Series Study and to provide data about voting and public opinion after the 2022 midterm elections in the United States.

"The ANES 2024 Pilot Study is a cross-sectional survey conducted to test new questions under

consideration for potential inclusion in the ANES 2024 Time Series Study and to provide data

about voting and public opinion in the United States."