A She-cession, then a He-cession, then just, a Recession.

The pandemic-induced recession hit women hardest first, but male employment was slower to recover

Note: I’ve teamed up with Will Secker for this post. (For which read, Will’s done most of the work). Will has just finished up at Northwestern studying both economics AND classics: my kind of guy, in short. We met when I spoke out there, and I'm delighted to say that we’ll be working together in the future: watch this space for more news on that front - Richard

In May 2020, the New York Times ran the piece “Why Some Women Call this Recession a ‘She-Cession,’” quoting C. Nicole Mason, president of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. The term became widely used to describe the economic downturn during the pandemic.

There was good reason at the start to worry specifically about the impact on female employment: just a couple of months after the pandemic hit, women’s employment had dropped 16% compared to 13% for men: both massive drops, of course.

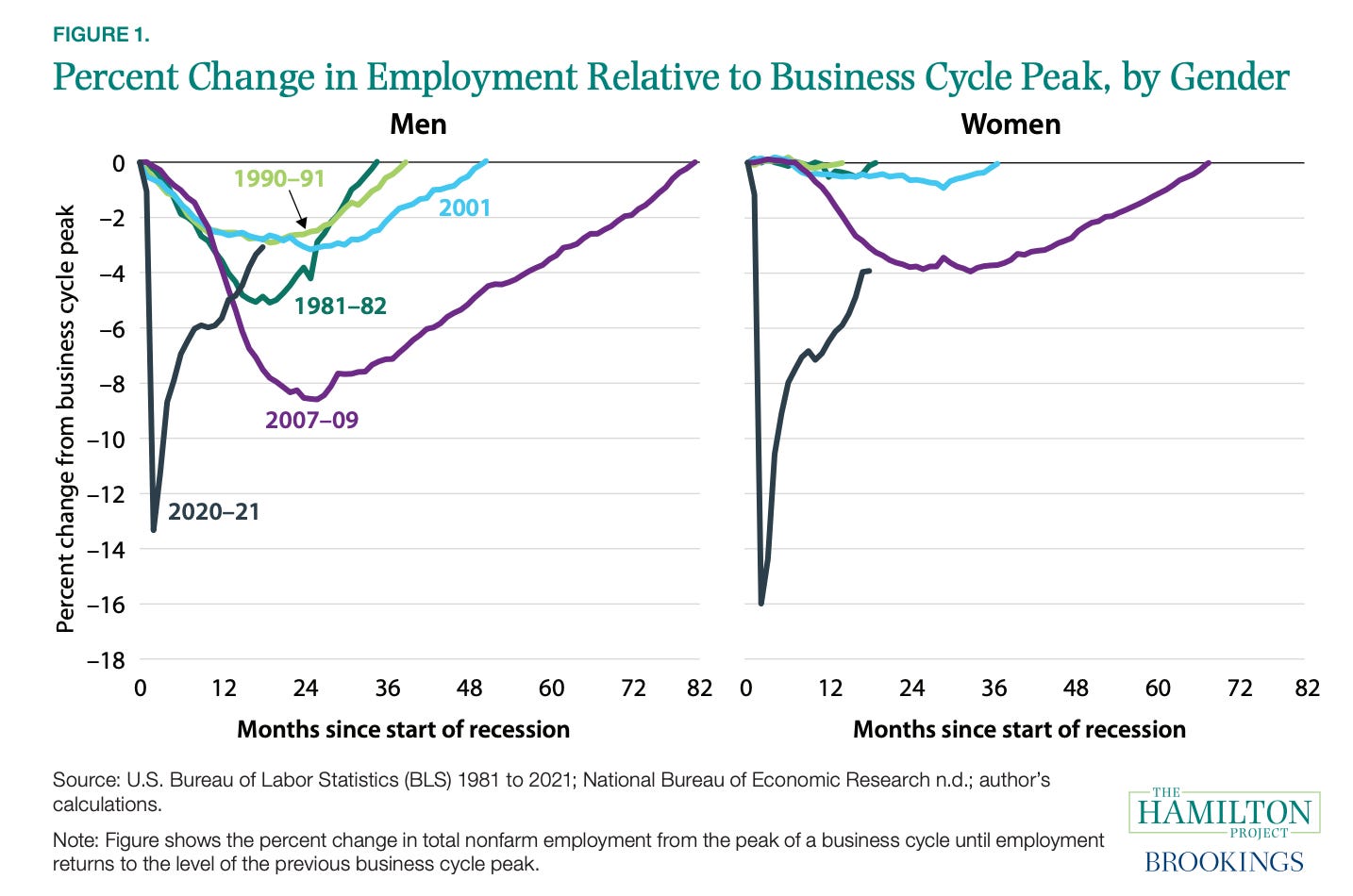

Yet the fact that this effect was even close to equal, let alone worse for women, made it so notable. As Betsey Stevenson showed in a 2021 assessment, the recessions of 1981, 1990, 2001, and 2007 were all very clearly “He-cessions,” hitting men’s employment significantly harder than women’s. Not only did employment fall more sharply for working men, but in each instance it also took at least 12 more months for men’s employment levels to recover compared to their female counterparts, as her chart shows:

As she notes, in December 2019, women possessed the majority of nonfarm payroll jobs in the US, a huge milestone that was the result of years of increasing women’s participation in the workforce. Thus, there were some common concerns brought up in the wake of the COVID recession:

“The erasure of decades of women’s progress in the labor market highlighted a real fear that the pandemic would set back women’s roles in the labor market. Would men go back to work while women stayed home? Had we entered a new era of gender inequality? Or would women return to work and to making further strides in achieving gender equality at work?”

(As we’ll see, it’s turned out to be much more the latter).

Why female employment was hit hardest first

Why did the pandemic-induced recession hit women hardest at the start?

The effect was primarily driven by 1) the kinds of industries most exposed to the pandemic and 2) the propensity of women to take up increased childcare roles in the home.

Women dominate jobs in the service sector, including in the retail, leisure, and hospitality industries. When the pandemic hit, demand dropped the most for these jobs that could not easily switch to remote work or required frequent in-person interaction. Men dominate in sectors like manufacturing and construction that require lower amounts of in-person contact and were thus less exposed to the direct effects of the virus.

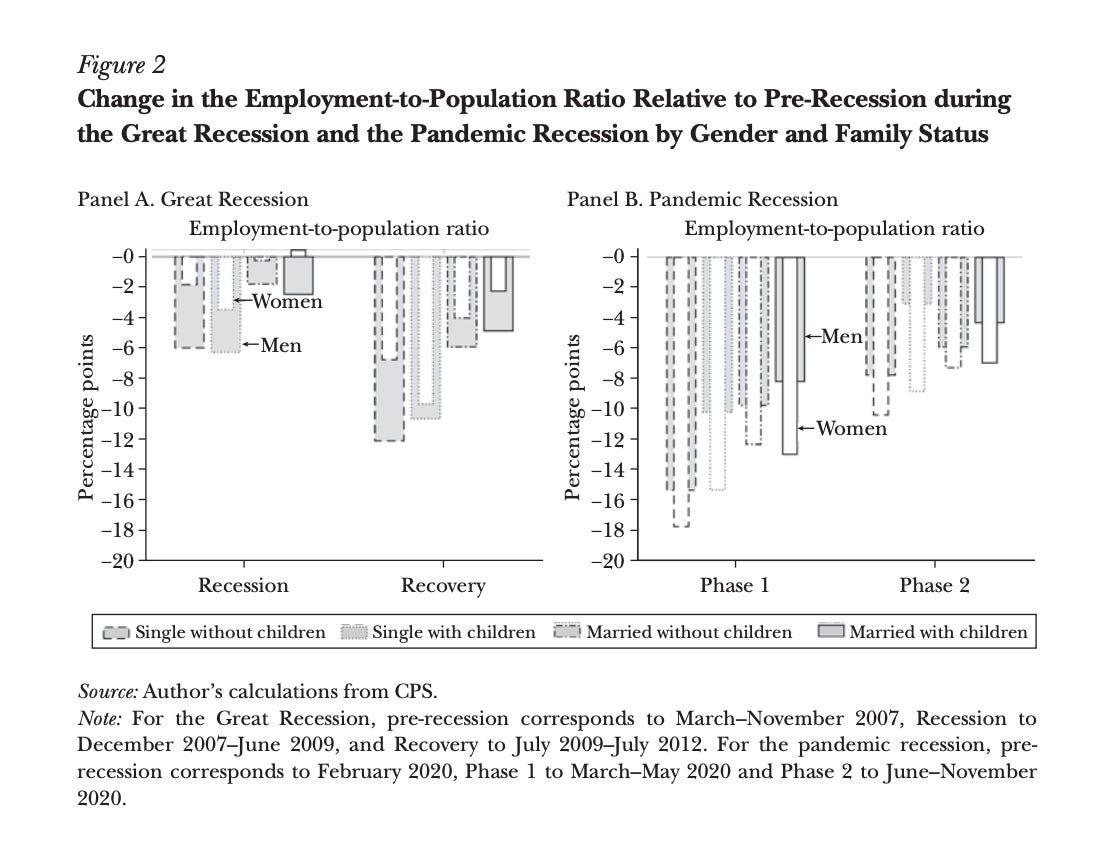

Additionally, women were more likely to leave the workforce to take care of children. The closure of schools and child care centers increased the need for supervision of children in the home, and mothers took on this role more than fathers. The EPOP (employment:population) ratio (share of the working-age population with a job) for both single and married women with children dropped significantly more than that for men in the same categories. Note the difference between the levels for the Great Recession and those for the Pandemic Recession.

So, the “she-cession” label was clearly appropriate initially.

But then things leveled out

As the economy recovered, the employment effects leveled out. By October 2021, the labor force participation rate (LFPR, similar to EPOP, except it counts those without a job but seeking employment) was still below the level of February 2020. Some of this was explained by more workers aging out of the labor force, but a decrease of 1.2 percentage points could be explained by workers just being out of the job market:

At this point, the decrease was “roughly equal” between men and women, according to Jason Furman and Wilson Powell. The gender difference disappeared over time. It seemed like it was neither a she-cession nor a he-cession. The economy started to rebound, and women went back to work.

Not only that, it looks like the fears that women’s progress in the labor market would be interrupted were not realized, at least in terms of seniority. Research from McKinsey and Lean In shows that between 2020 and 2022 the share of women at most levels of management increased:

The rise was especially encouraging at the top: the share of C-suite executives who are women increased from 21% to 26% in those two years.

Wait, what’s up with male employment?

By late 2022, some commentators were started to worry more about men. In December 2022, the New York Times published an article examining the recovery from the recession for men, specifically between the ages of 25-54, those whom economists consider “prime-age workers.”

The Times included the story of Paul Rizzo, a 38-year-old former analyst for a hospital company, whose job was automated near the end of 2021. He left the workforce to watch his kids while his wife went back to work; she was part of the female demographic that was on the upswing from the lows of the recession.

At the end of 2022, LFPR was almost back to pre-pandemic levels across each female age bracket between the ages of 25-54. This was good news; women’s participation rates kicked back up hard in 2021 and kept on rising. But that didn’t seem true for some men:

And in that specific age group, 35 to 44, men both with and without college degrees seemed to be slower to return to work:

Middle-aged workers in the 35-44 age bracket are supposed to be in their prime working years. College degrees are supposed to help provide marketable skills and help with job placement. So why was this key demographic faring no better than at the post-recession lows?

One explanation offered by the Times reporters is that the 35-44 age group is made up of those who were fresh on the job market right as the Great Recession hit in 2008:

“Some economists speculate that the disproportionate decline could be because the age group has been buffeted by repeated crises, making their labor market footing fragile. They lost work early in their careers in 2008, faced a slow recovery after and found their jobs at risk again amid 2020 layoffs and an ongoing shift toward automation.”

If this explanation is true, it is a bleak scenario: one where millions of men are left fragile in the job market because of one crisis after another. Labor force participation for prime age men has already been falling for decades. For the 35-44 age bracket, when almost all men are supposed to be working, LFPR is down from highs of 98% in the 1950s to 90% as of April 2023. The pandemic caused this level to dip below 90% for the first time in measured history.

Indeed, on the whole, the continuous decline in male LFPR over time, and the corresponding rise in women’s participation, has been a much-talked about phenomenon. The fact that the pandemic accelerated this decline to the lowest overall level ever is significant.

The Times article finishes: “It feels like it’s the aftereffects of 2008 and 2009,” [Paul] said. “Everyone had to restart their lives from scratch.”

One of the themes of Of Boys and Men is that in order to accurately prescribe policy solutions, we must accurately diagnose the situation on the ground.

The story of the Covid recession is one of timing: female workers were hit harder than men initially, due to a combination of the way certain types of jobs were exposed and an increased childcare burden. But over time, they went back to work. Meanwhile, participation for middle-aged men stagnated.

Better news, now

Especially during an economic shock it is important to look hard to see which groups are faring the worst at different points and why. It’s clear that the care infrastructure in the U.S. is woefully inadequate for a world where most parents, female as well as male, are in the labor force. At the same time, the long-run trends for male employment rates are deeply troubling, and have very different causes.

It is very important to update our perceptions with the latest data. Some folks are still using the language of “she-cession”, long after the term was accurate. And what about those 35-44 year old men? There too the recent trends look better. Since the Times article, LFPR for 35-to-44-year-old men has ticked upward, along with every other age group, both male and female.

It appears that this might be the last push up out of stagnation and above pre-pandemic levels for most groups. Certainly let’s hope that’s the case.

After all the analyses and headlines and fears, it looks like the post-pandemic labor market might look remarkably similar to the pre-pandemic one. Which of course is not the same as saying that it’s OK. It just means that the longer-standing concerns about the labor force participation rates of both men and women should move back to the top of the agenda.

What started as a she-cession might leave a legacy of lower male labor force participation. Surprising to me. Although we're still waiting for the final analysis.

Here in Australia, we had very similar media reports. But, on closer inspection, things were not what they seemed.

To me, the striking thing about the early Australian reports was that they were using data on employment to draw conclusions about which sex was hardest hit. Normally, unemployment (or perhaps underemployment) data would be use for this purpose. (I think these comments may also apply to the US.) I was intrigued enough to look more closely. Very briefly, what I found was:

• Women mostly didn’t "lose" their job, they resigned. And they mostly chose not to look for a new job - moving from employed to "Not in Labour Force".

• Women did not give up work because of increased domestic demands. During Covid, men increased their time spent on domestic activities by 34% while women’s time didn’t change.

• More men were laid off than women. Men also lost more hours of work and more wages.

These conclusions are based on data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (only). You can learn more here: https://www.bettinaarndt.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/The-Pink-Recession-and-The-Gratton-Institute-report.pdf If more details are needed, please feel free to ask.

It would be interesting to know whether any of these findings for Australia also apply in the US.