American men are dying younger.

It's about time to create an Office of Men's Health, as a new Bill proposes

I was talking to a friend the other day about how bad the Covid-19 pandemic had been for men, not least in terms of mortality rates. She did not dispute the facts. But she emphasized how stressful the pandemic had been for many women, especially working moms in the first months. (It was).

At once point she said, “Yes, of course death is bad, but. . .”

Death is certainly bad. It is arguably the worst outcome measure available to us. It was the kind of comment that makes some men feel like their lives are seen as worth less, the so-called “disposable male” thesis. That is not what I felt. I know my friend thinks her husband and her son have lives that are as precious as her own, and her daughters’.

Rather it was an illustration of how hard it is for any of us to hear the other side of any given story and not be thinking inwardly, “yes, but what about….?”

It’s easy for me to say that we can think two thoughts at once. And I do say that, a lot. But it’s actually not that easy to do. When it comes to gender issues, partisans especially are primed towards what-aboutism.

It is a simple fact that boys and men are at a much higher risk of dying than women, and that we die much younger, on average. In the U.S, the life expectancy gap just widened to six years, the highest since the mid-90s.

There’s a tendency for people to note the gap, and then move on, perhaps thinking something along the lines of: “Well, everyone knows women live longer than men”.

But in fact the gender gap in life expectancy varies considerably by time and place. At the beginning of the 20th century the gap in life expectancy in the U.S. was just two years, and the gap remained at around this level until the post-war years when men fell behind:

The main reason for the widening of the gap in the middle of the century was that men smoked more than women, and so were dying more from cancer, especially lung cancer.

There is also a lot of variation by country, as this map from Our World in Data, showing the gender gap in life expectancy in 2021, shows:

These trends and differences suggest that the life expectancy gap between men and women is not a simple fact of biology. That claim would, after all, be a very strong form of biological determinism! It suggests that in fact there is a strong role here for social and economic conditions, and therefore for public policy.

Widening gender gap in life expectancy

In 2021, projected life expectancy in the U.S. was 73.5 years for men and 79.3 years for women. The gender gap of 5.8 years was a full year wider than the 4.8 year gap reported in 2010, according to a new study in JAMA Internal Medicine, which drew on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The gap widened by 0.23 years between 2010 and 2019, largely because of men’s higher risk from “deaths of despair”, including opioid overdoses and suicide (on which, more below). Then when the pandemic hit the gap widened much more, by 0.70 years from 2019 to 2021, because men were at a much higher risk from Covid.

The chart below from the paper shows the contribution of various factors to the widening of the gap. Panel A shows 2010 to 2019. Panel B shows 2019 to 2021.

A few key points to draw out here:

The narrowing of the gender gap in cancer deaths has been the main positive factor in terms of the overall disparity in life expectancy.

Until 2019, the main cause of the widening gap was the much higher male death rate from unintentional injuries, which includes overdoses and accidents.

Covid-19 accelerated the widening of the gap in very recent years, making the biggest contribution since 2019.

Even without the pandemic, the overall life expectancy gap would still have widened, just not as rapidly.

Before 2019, the greater male death rate from suicide mattered more for the gap than homicide; since 2019, homicide has played a bigger role, reflecting the recent surge in violent crime.

Whatever the causes, the reversal of progress in narrowing the gender gap in life expectancy is a serious cause for concern. “It was unsettling to see,” said Dr. Brandon Yan, lead author of the study.

Covid, Manslayer

As the new study makes clear, many more men died from Covid than women. At the last count 632,000 American men had died from the virus, compared to 520,000 women, a difference of 110,000 lives. That’s about the population of Peoria, IL or Tuscaloosa AL.

The gender gap is even starker once age is taken into account. More than half the Covid deaths (54%) were among the over-75s. This age group skews very female: there are 14 million women over the age of 75, compared to 10 million men.

For this reason, a better measure of the gap is the age-adjusted death rate, which has been very much higher for men. The chart below shows CDC data on the age-adjusted mortality rate for men and women in 2020, 2021 and 2022:

Among middle-aged Americans, the gender gap was almost 2:1. In the 30 to 50 year age group, 41,000 men died compared to 25,000 women. In fact the higher death rate among men is one reason the male labor force has shrunk in the last few years.

The disproportionate male death rate was even more pronounced in major American cities, where men were 78% more likely than women to die, and amongst minority populations. Research in California found that male workers had an age-adjusted mortality rate 3 times higher than female workers, compounding disparities for Black and Latino men.

The male suicide crisis

Suicide rates are four times higher among boys and men than girls and women, and are rising. I’ve written about this before, and AIBM has a research brief on this topic. So here, I’ll just point out the important shift around 2010. Before then, the rise in male suicide was concentrated among middle-aged men. Since 2010, the rise has been entirely among young men, aged 15-34, as this chart shows. (Note that it shows the rate of increase, not the rate, which remains highest among older men):

The male suicide crisis is only a small part of the story of falling male life expectancy. But it has huge social consequences, not least when the victims are so young, and arresting this rise should be a priority for policymakers.

Time for an Office of Men’s Health

Brandon Yan, lead author of the life expectancy study, says that it should act as a wake-up call for health policy. He said:

We need to understand which groups are particularly losing out on years of life expectancy so interventions can be at least partially focused on these groups... Future research ought to help focus public health interventions towards helping reverse this decline in life expectancy.

Yan went on to suggest that especially in areas like mental health, more attention should be paid to the case for specialized care for men.

As you might imagine, my response to that idea is: Amen.

But a necessary first step is to create some institutional architecture around men’s health. The lack of awareness of men’s health problems creates a lack of political will to address them, which in turn undermines support for male-focused health care.

That cycle must be broken. And maybe it will. In June 2023, the Men’s Health Awareness and Improvement Act was introduced to Congress by New Jersey Democrat Donald Payne, with 14 co-sponsors, all Democrats. (I’m hoping the absence of Republican co-sponsors does not indicate an absence of Republican concern for men’s health).

The Bill would create an Office of Men's Health within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), charge the Assistant Secretary for Health with studying men's use of health screenings and services, and instruct the Government Accountability Office to report on the effectiveness of federal outreach related to men's health initiatives.

The new Office would mirror the existing Office on Women’s Health in HHS. There are in fact a number of other initiatives and agencies focused on women’s health, including:

The Office of Women’s Health in CDC;

the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) working to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA);

Regional Women's Health Analysts working in the 10 regional health offices around the country; and

the new White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, launched in November 2023

This is not an exhaustive list, and only covers national government: there are many similar agencies and initiatives working at a state and local level.

All of them do valuable work on behalf of women and girls. It is thanks to the work of institutions like this that the Government’s Healthy People 2030 Initiative, working out of HHS, has set 29 health targets for women, ranging from breast cancer and osteoporosis to smoking during pregnancy. There are also 18 targets for LGBTQ people.

For men, the number of official health targets is. . . four.

Three of these relate to about sexual health and contraception: reducing gonorrhea, reducing syphilis, and increasing condom use among young men. The fourth is reducing death rate from prostate cancer.

This is a glaring disparity in official health goals for the nation, especially in light of the wide and growing life expectancy gap between men and women, and the high and rising risk of death from suicide for boys and young men.

The targets for LGBTQ people include reducing suicidal thoughts among LGB and transgender youth. This is a good and important goal. But strikingly, the targets for men do not include reducing actual deaths from suicide, even though in 2022, about as many men died from suicide (40,000) as women did from breast cancer (42,000).

I don’t think this is because the officials at HHS don’t care about boys and men. I think it is because there are no official agencies in government with a specific focus on the health of boys and men, advocating on their behalf.

The proposal for an Office of Men’s Health is not new. The idea has been around for some time. But given recent trends, it sure seems like an idea whose time has come.

Reeves is right on track. The outcomes for boys and men are startling. In a number of educational meetings with policy makers, there is always a pause when it comes to deaths of despair (suicide, overdose, and alcohol deaths). Most policy makers do not know that 80% of suicides, 70% of overdose deaths, and 69% of alcohol deaths are male. This has happened time and time again. Policy makers are unaware because they are not educated on the subject. It's the reason an Office of Men's Health is so critical.

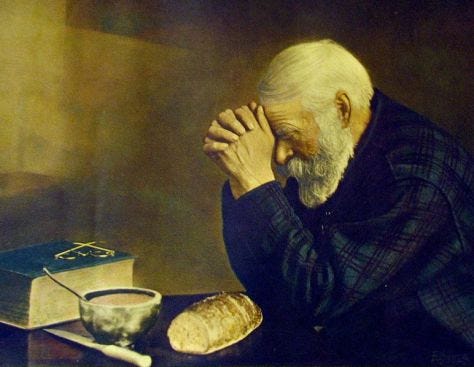

One of the big big big issues that needs to be grappled with is that women can not care and love men into caring and loving themselves. Trust me, I have tried. I simply work harder at my mental health than just about every man I know, save the ones who are trying to be Tony Robbins.

I love men, I care deeply about the mens health crisis as does every woman I know. But when the men in our actual lives refuse to go to the gym, on a walk, an healthy meals and go to therapy...it is really hard to continue generating the emotional energy to see this as a problem we can do anything to solve.

And just like solving women's and girl's attainment disparities took a lift from both genders...so will solving this for men. But good lord...our husbands have to do the work of participating. The everydayness of improving mental, physical and spiritual health is HARD.