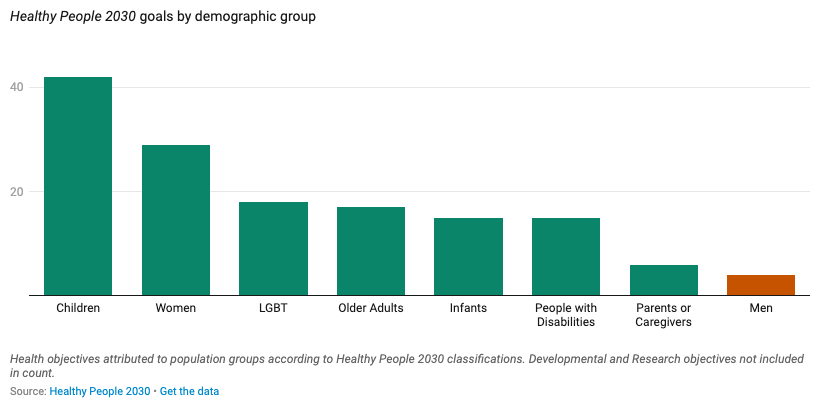

Every ten years, the U.S. Federal Governments sets out health targets for the next decade. The latest, Healthy People 2030, were released in 2020. There are 359 core health benchmarks, many of which relate to particular demographic groups. The chart below shows how many goals have been set for each:

There are 4 for men.

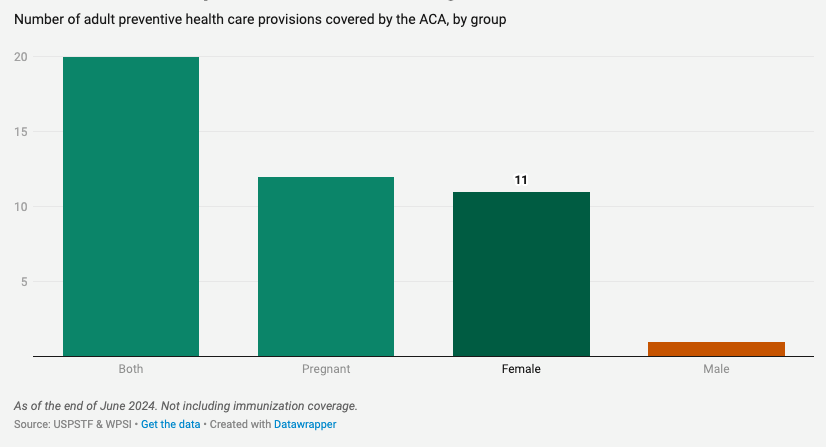

There’s also an asymmetry in the provision of preventive health care. As I write, there are 44 preventive health care interventions for adults covered under the Affordable Care Act (excluding vaccinations). Some of these are for everyone, while some are for specific groups. Twenty apply to both sexes, 12 relate to pregnancy, 11 apply to women (and are unrelated to pregnancy):

One applies only to men.

(In case you’re wondering, it is screening for an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm among men aged 65-75 who are smokers or former smokers).

The strong focus on women’s health is result of the work of many people and offices within the corridors of power. There are a number of Federal institutions and initiatives on this front, including:

Office on Women’s Health, Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

Office of Women's Health, Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA)

Office of Women’s Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Office of Women’s Health, Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Office for Research on Women’s Health, National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Initiative on Women’s Health Research, The White House

Gender Policy Council, The White House

Regional Women's Health Analysts working in ten regions

Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women (NIH)

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (HRSA)

The problem is not the excellent work being done for women’s health; it is the lack of work on men’s health. This is particularly striking given recent trends.

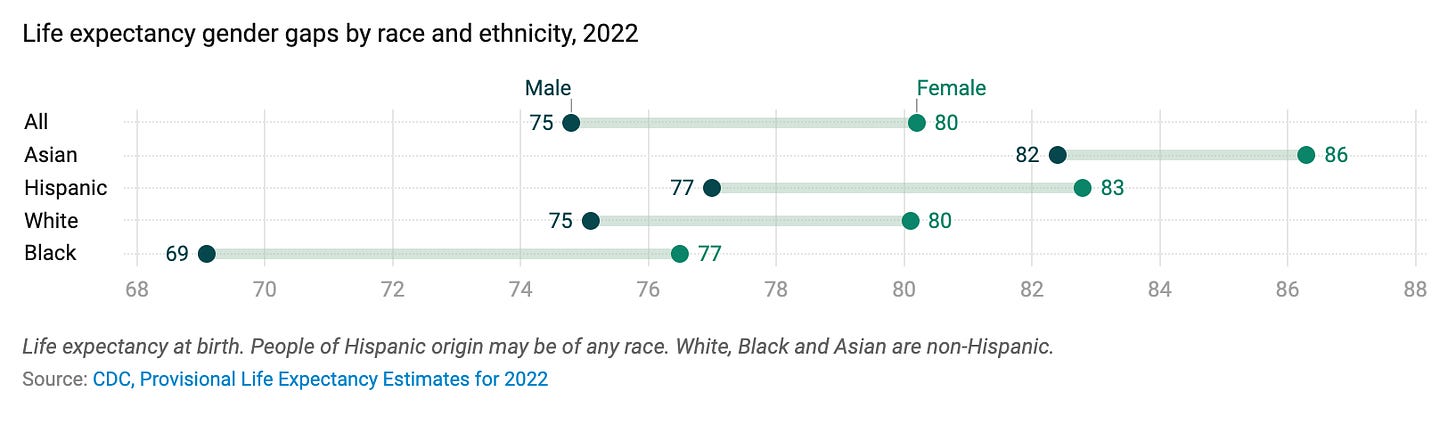

Gender gap in life expectancy

I’ve written about this before, but it’s worth repeating that there’s a large gap in the lifespans between men and women in the U.S., wider than in other nations and wider than in the past.

(For more on this and most of the data in this post, see AIBM’s just-published “Six Facts on Men’s Health”).

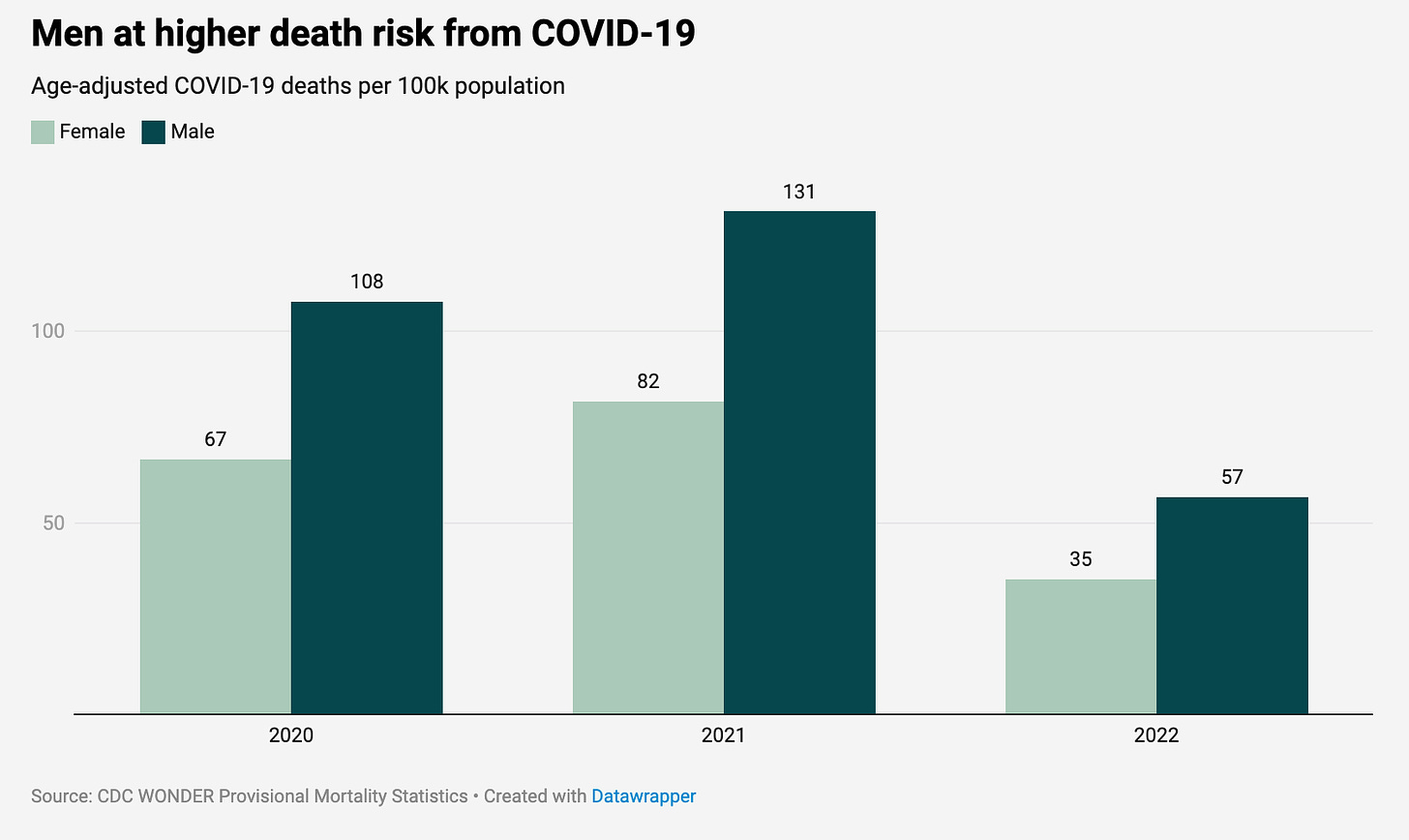

Why? Partly because a lot more men died from Covid-19:

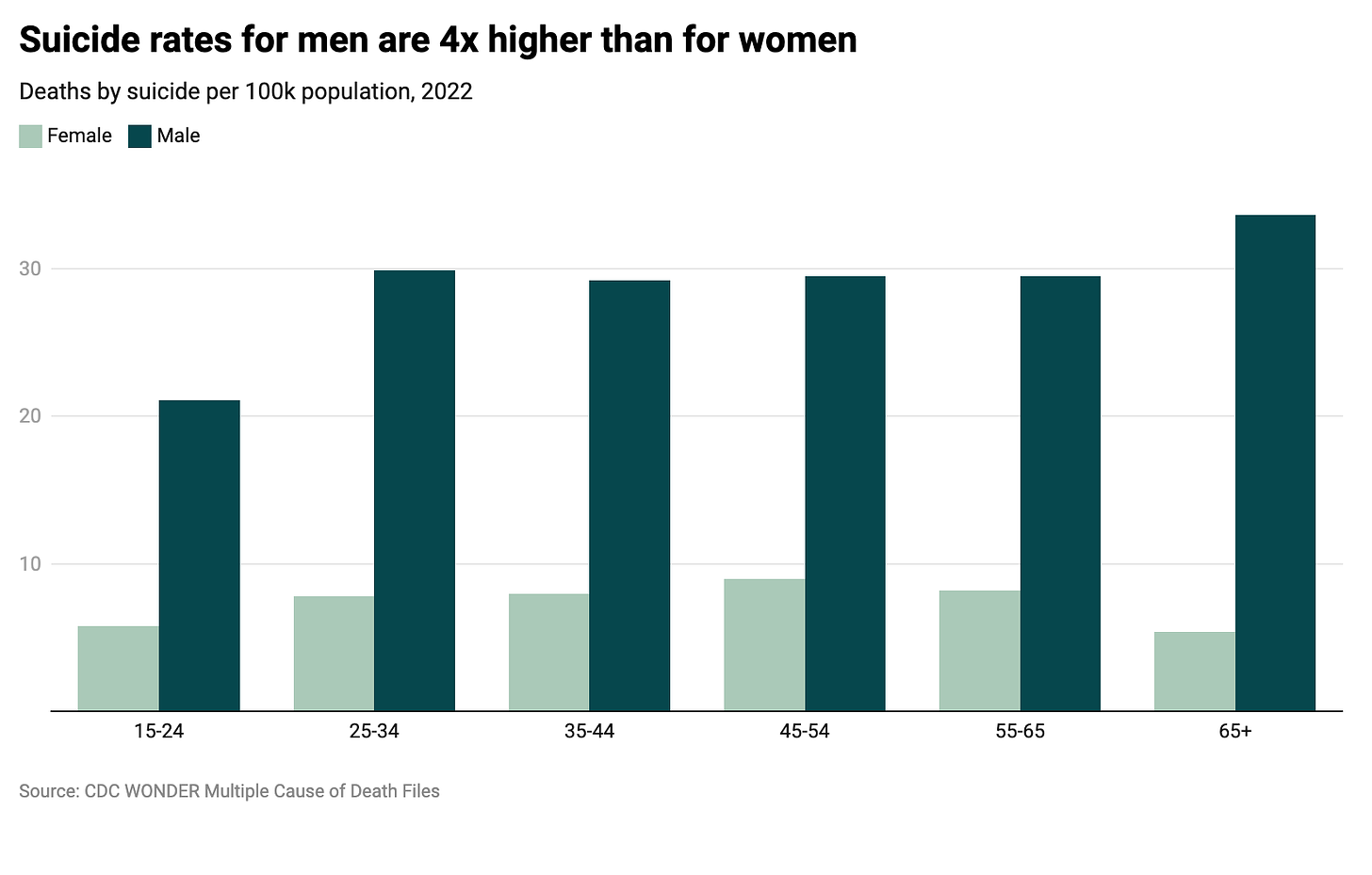

Partly because men are at a much higher risk of death from suicide:

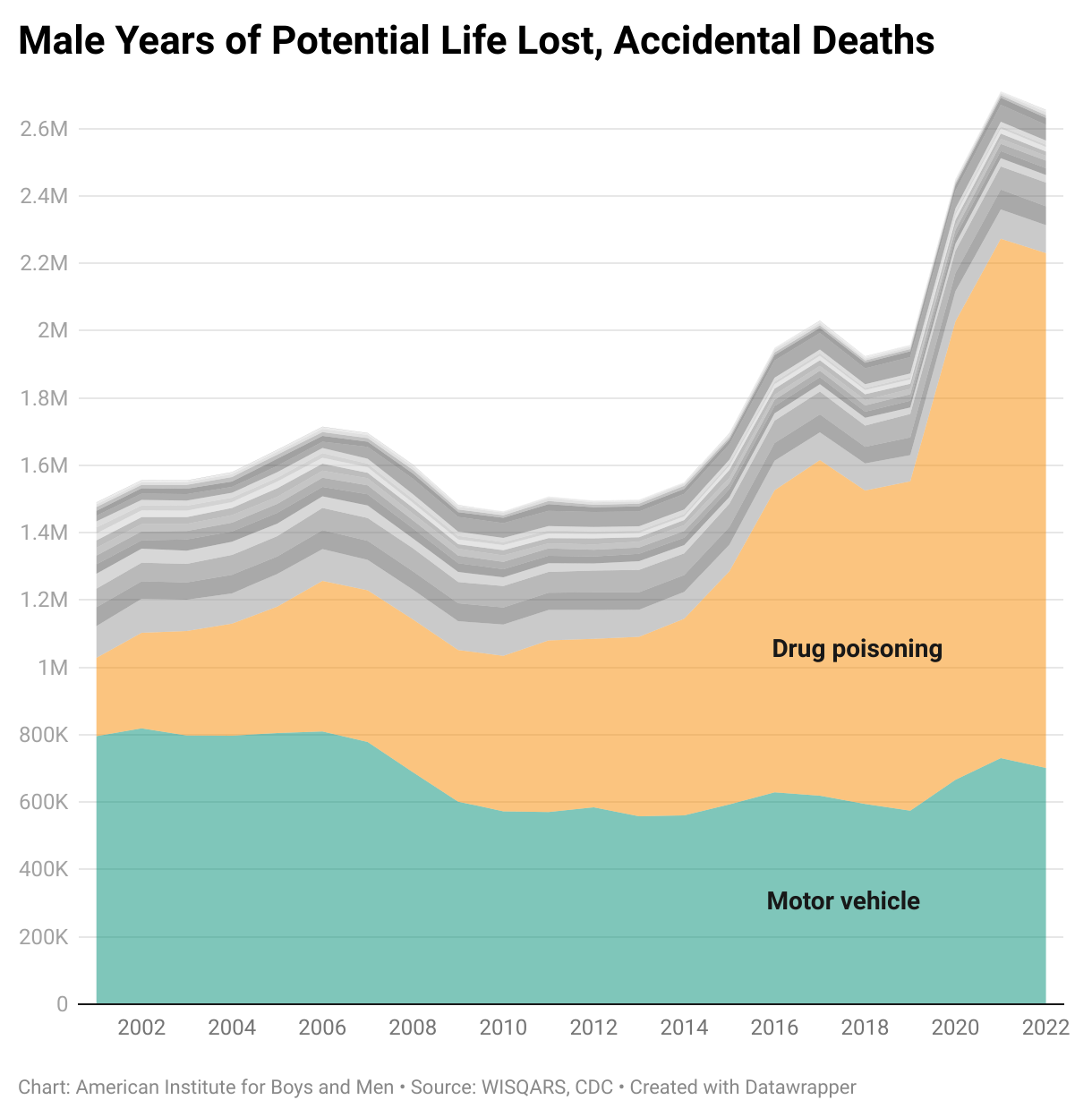

Drugs more than driving shortening men’s lives

One fascinating CDC data series shows the potential years of life lost each year as a result of deaths from injuries and accidents occurring before the age of 65. The calculation is intended to put more weight on an earlier death from a non-natural cause; a person who dies at the age of 25 loses 30 more years of potential life than if they were to die at 55.

The CDC data, reaching back to 2001, shows that around three times as many potential years of life are lost for men as for women. In 2022, more than four million years of potential life were lost for men, and almost one and half million years for women:

Back in 2001, car accidents took more years of life from men than drugs. As cars have become safer and drugs more prevalent, that has reversed:

There’s lots more that could be said, and over at AIBM we’re super-focused on these health issues for men, especially in terms of mental health. But is already clear that men’s health ought to be a big priority for policymakers.

A few leading the way

Some states and localities are showing the way:

North Dakota is pioneering here: in 2021, the North Dakota Department of Health and Human Services created a Men’s Health Program with a mission “to improve health and well-being in men and boys by increasing access to education, health care and behavioral health services, and support statewide.” The Program is currently focused on improvements in data collection and sharing, behavioral health including mental health, and fatherhood. The state has also appointed a Men's Health Coordinator.

In Utah, the new Governor’s Task Force on the Wellbeing of Men and Boys aims at “helping men and boys lead flourishing lives”. While the Task Force has a broad remit including education and employment, it also includes the goal of improving physical and mental health for boys and men in the state.

In Massachusetts, MassMen, a suicide prevention program, encourages “working-age men across MA to take action to feel better emotionally, physically, and spiritually.” The program provides resources for tackling a host of issues faced by working men, as well as free MassMen trainings, and services to businesses.

There are also some hospital-based programs, such as the UNC Men’s Health Program which aims to tackle “the silent health crisis among men”, through research, community outreach and clinical care. The Program produces an annual health Report Card for men in the state.

There are also some more clinically-oriented initiatives, such as the Preston Robert Tisch Center for Men’s Health at NYU.

Time for an Office on Men’s Health

At a conference a few months back, an audience member asked some scholars on sex differences whether, given some of these trends, they supported the creation of on Office on Men’s Health in the federal government. One immediate response was “It’s called the CDC!”

But if was true that the CDC and other health agencies took men’s health more seriously than women’s health, it is hard to say this is true today. I could be wrong about this, but I honestly don’t see much evidence for an anti-female gender bias in the work of HHS, or CDC, or NIH.

This does not mean that the women’s offices and initiatives should be abolished. There is a strong case for charging some institutions with taking a gender-sensitive approach to the analysis of health trends, in the design and evaluation of research, and in the formulation of health policy.

Instead, it means creating similar institutions focused on men’s health, including an Office on Men’s Health in HHS. (There is a bill to do just this in the House Representatives). At this point it is hard to see strong arguments against it.

The motto of the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative is:

When women are healthy, communities thrive.

That is absolutely true. But it is equally true that communities thrive when men are healthy. As Derek Griffith, director of Georgetown University’s Center for Men’s Health Equity in the Racial Justice Institute says:

We tend not to prioritize men’s health, but it needs unique attention, and it has implications for the rest of the family. It means other members of the family, including women and children, also suffer.

The question that must be answered is why there is so little attention to men's health and why would that person think the entire CDC was for men. The answer is actually simple but no one wants to admit it. It's called gynocentrism. We are living in a world where the needs of women, the feelings of women, the safety of women is at the top of the list while the same issues for men is at the bottom. This post is a good example of this dilemma.

The first step in dealing with this mess is to help people become aware of this truth. At this point no one believes in such a thing but just look at the facts of this post and you will have to admit there is something going on.

For more info on gynocentrism there is a great site http://gynocentrism.com that goes into great detail on this. Or you can click my username above and come to menaregood.substack.com lots of good info there also.

Per my earlier post...

Men's health initiatives were proposed in Congress at least 15 times since 2000:

H.R. 4653 (106th): Men’s Health Act of 2000

S. 2925 (106th): Men’s Health Act of 2000

H.R. 632 (107th): Men’s Health Act of 2001

S. 2616 (107th): Men’s Health Act of 2002

S. 1028 (108th): Men’s Health Act of 2003

H.R. 1734 (108th): Men’s Health Act of 2003

H.R. 457 (109th): Men’s Health Act of 2005

S. 228 (109th): Men’s Health Act of 2005

H.R. 5624 (109th): Men’s Health Act of 2006

H.R. 789 (110th): Office of Men’s Health Act of 2007

S. 640 (110th): Men’s Health Act of 2007

H.R. 1440 (110th): Men’s Health Act of 2007

H.R. 2115 (111th): Men and Families Health Care Act of 2009

H.R. 5986 (117th): Men’s Health Awareness and Improvement Act (2021)

H.R. 4182: Men’s Health Awareness and Improvement Act (2023)

None of these pieces of legislation ever received a vote. Also, Rep. Donald Payne (D-NJ) was the sponsor of the latest attempt and he just tragically died from cardiac arrest, which was precipitated by high blood pressure and diabetes. Diseases that this type of legislation would try to stop.