What a wonderful day this is! I am filled with hope, gratitude, admiration and joy. I am filled with love for every human being on the planet. In a zoom meeting earlier, I literally broke out into song. Then I got a bit tearful.

Perhaps the strain of advocating for boys and men has finally caused me to breakdown? No it’s not that. It’s this:

A Norwegian Government Commission just issued its final report.

But not just any Commission. It is the Mannsutvalgets, or Men’s Equality Commission. Last year, I was honored to address the Commission at some private events, and one public event.

Honestly, I was thrilled that it was even established, and with full status and government support too, founded by Royal Decree on August 26th, 2022. The creation of the Commission is proof that countries truly committed to gender equality are waking up the fact that, now, this means paying some attention to the inequalities impacting boys and men. If Norway can do it, you really have to ask why other nations and states still struggle with the idea. (Norway ranks 2nd in the world on women’s rights).

I hoped the Commission would be able to put forward a modestly positive case for working on behalf of boys and men. But they did so much more. The final report, titled Equality’s Next Step, is a doorstop of a volume: a comprehensive, factual, policy-rich manifesto for boys and men in a society committed to gender equality. It sets a standard for policymakers around the world who are interested in tackling this issue.

Here’s the Commission Chair Claus Jervell presenting the report to Culture Minister Lubna Jaffery:

Getting the framing right

Crucially, the Commission frames the issue in exactly the right way.

First, there is a clear rejection of zero-sum thinking. Working on behalf of boys and men does not dilute the ideals of gender equality, it applies them. Here is how the Commission sets out their stall:

Many boys and men do not feel that equality is about them, or exists for them. The men's committee believes that equality's next step should be to include boys and men's challenges to a greater extent than today. . . Greater attention to boys' and men's equality challenges will strengthen equality policy, not weaken it.

Second, the Commission stresses the need to look at gender inequalities for boys and men through a class and race lens too. As the Commissioners write:

Social inequality is an important factor in understanding these differences. Some challenges are linked to class and social inequality and affect boys and men harder or in different ways than girls and women.

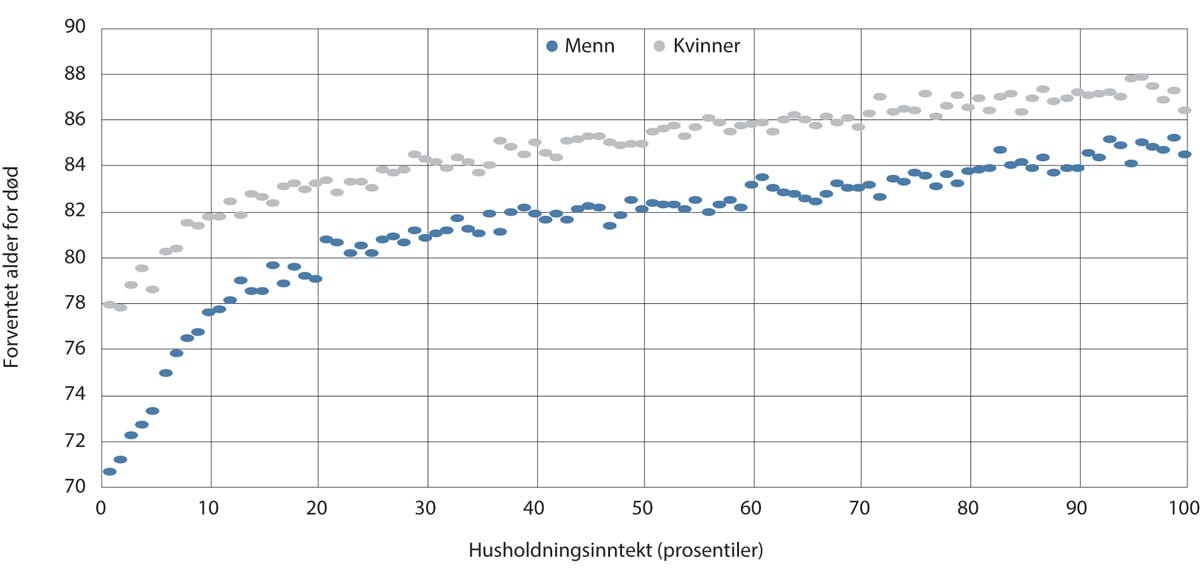

A good illustration is the class gap in life expectancy. The gap between affluent and low income women is 8 years: but for men, the class gap is 14 years. Another is the finding that men with a Pakistani background face more discrimination in hiring than women with the same background (though both face some).

Third, the work of the Commission, and its resulting recommendations, is firmly rooted in evidence. There are data-rich chapters on family life, education, work, leisure, health, crime and social isolation.

As Helene Aarseth, professor at the Center for interdisciplinary gender research at the University of Oslo, points out, the report is “written in a calm and non-aggressive tone”. That’s true. And it’s vital: tone matters.

Making the case with data

The report offers an excellent and balanced summary of the evidence for gender gaps in a wide range of areas, with a strong bias towards quantitative studies. I’ll just highlight a few here, by way of illustration (and, I hope, inspiration).

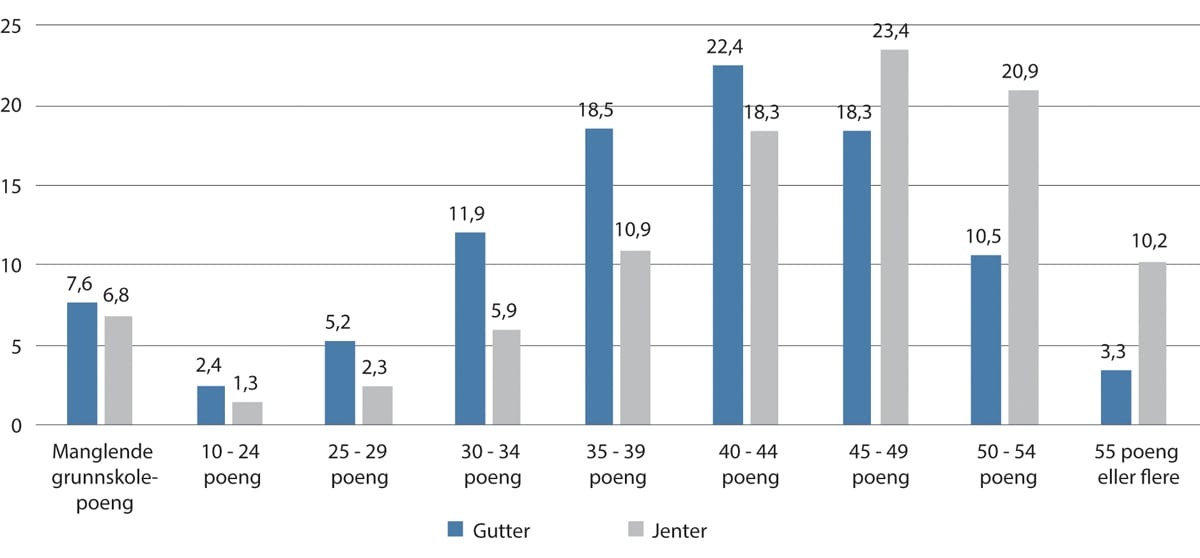

In Norway, elementary school progress can be measured in “credits” and this chart shows the gender distribution from lowest on the left to highest on the right. 70% of those at the bottom are boys, while the reverse is true at the top:

The Commission is especially strong, I think, in its identification of health inequalities. These show up in the difference in life expectancy, as shown in the chart below (this is life expectancy at the age of 40 by gender):

The Commission states bluntly that “it is an equality challenge that men in Norway live shorter lives than women.” I agree. But in most studies of gender equality, the gap in life expectancy is simply treated as a given, rather than as a gap.

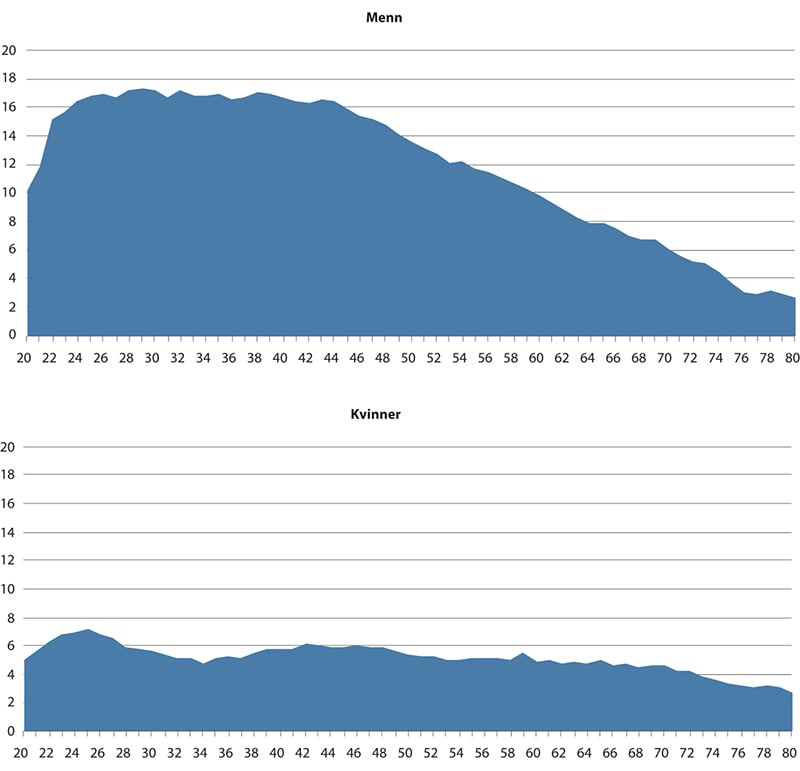

A big challenge here is that women have what the Commission calls a “front door” to health care, largely as accessing reproductive care services. As a result, men are much more likely than women to not visit a doctor during any given year, especially when they are younger (the chart shows the proportion with no visit in a given year, by age, for men and women):

The Commission also points out while men have only a slighter higher risk of occupational injury, they have a much higher likelihood of dying as a result of a workplace accident. In fact, as the report notes with an indicative tone of understatement:

It is almost only men who die in fatal accidents at the workplace. In the period 2015–2019, 97 per cent of all those who died in occupational accidents were men.

Strong recommendations

In Equality’s Next Step, the Commission makes a number of important recommendations. I’m sure I’ll be referring to some more of these in future posts, but for now I’ll highlight a few that struck me most strongly on first reading:

Equal paid leave. Norway has very generous parental leave, but skewed towards mothers. The Commission proposes that mothers and fathers have equal, independent leave rights: “Splitting the leave into two can act as a standard setting and is a clear signal from the public that mother and father are just as important as carers.”

Flexible school start. The Commission proposes that parents have right to delay school start for their children (or “redshirting” in U.S. terminology): “The committee considers that the measure has the potential to equalize gender differences in school results, as there are gender differences in the development of a number of characteristics that are associated with school performance, such as self-regulation.”

More men studying for careers in health, education and social care. What’s needed, the Commission writes, is: “a comprehensive and long-term national initiative to recruit boys for health, care, social and educational subjects in higher education”.

Men’s Health Committee. This institutional reform has a timeframe: “A men's health committee [should] be set up in the current parliamentary term to carry out a closer investigation of men's health challenges and gender differences in health.”

Gender neutral equality law. The current Equality and Discrimination Act in Norway states that it is “particularly aimed at improving the position of women and minorities”. The Commission believes that “this provision should be made gender neutral by removing the words ‘women's and’ from the law.

The Commission also calls on the Research Council in Norway to explicitly take up the challenge of improving the knowledge base on many of the issues tackling in the report. And as a pretty wonky bunch, they are keen on more data transparency too, calling for “a review and revision of the statistics pages and indicators for gender equality so that they reflect the equality challenges of boys and men to a greater extent than today.” That might sound dull: but honestly, just getting the basic facts in front of more eyes is a powerful and often necessary first step to action.

I applaud these proposals. And in many cases, there are similar potential reforms that should be considered in U.S., whether at federal, state or local level. But for now, it’s Norway’s day.

Tusen takk

I don’t know how many of the Commission’s recommendations will be adopted by the Norwegian Government. The reception so far to the report seems to have been positive, (see here and here for example), so there is cause for optimism.

But I think the work of the Commission has significance well beyond Norway. There are policymakers around the world trying to figure out how best to begin to approach the glaring, growing problems of boys and men. Now they have a blueprint.

So thank you, to the Norwegian Government for founding and funding the Commission, and of course to the Commissioners themselves. I’ve worked in government a bit, so I can tell the difference between the report of a Commission that dialed it in, and of one that dug in. The report is proof that they took their charge very seriously indeed, and worked extremely hard to get the report into such very fine shape. But I’ll also do the thing you’re not really supposed to do and give my thanks to the civil servants who worked on the Commission, and especially the Secretary, Kristian Landsgård. I spent some time with Kristian in Oslo, and all I can say is that the Norwegian Government is lucky to have him: dude rocks.

As Roosevelt said in 1942, in an admittedly different context: Look to Norway!

Great that the report was written in a "calm and non-agressive tone" and that it went beyond expectations. We who want to help in this domain can take a lesson from it. I've been inhabiting some of the man-woman conversation in "X" and the rhetoric there, at least where I'm looking, is often inflammatory.

This is just a step but a step with a spring in it. Great news indeed!

Norway casts a brilliant vision for how to focus our attention on men and boys without demonizing women and those who continue to work for the equality of women and girls. The move away from zero-sum thinking seems to be the critical first step in any initiatives getting off the ground. Metaphors of the swinging-pendulum (it's gone too far!) or the failure of one-side or another (Progressive policies have failed!) just lead to this sense that any attention given to men and boys will necessarily take it away from women and girls. But, thankfully, we're seeing a move in this report toward a Both/And approach to gender equity. (This seems the consistent stance of the AIBM as well.)

As for how helpful this can be for the US: the size of Norway's population is irrelevant. Their population is no smaller, nor more homogeneous, than many US states. Norway has an indigenous population (the Sami) and has had considerable immigration for many decades. They're experiencing many cultural shifts (as the Muslim population grows very rapidly) and generational gaps just as the US has.

Their work in this commission is an excellent example for every country. Thanks for helping it to gain wider attention. It will be extremely interesting to see what sorts of social policy initiatives come from it!