Willful ignorance of the male suicide crisis

Even the experts and top-tier publications won't state the facts plainly

I’m a fan of Andrew Solomon; his book on depression, The Noonday Demon, remains the best on the subject that I know of. It helped me both intellectually and personally. I also strongly recommend “New Family Values”, his Audible series on the changing shape of family life.

So I was delighted to see that Solomon just had the cover story in the New Yorker on the “Teen Suicide Crisis”. As expected, it’s a deeply-reported essay grappling especially with the impact of new technologies on the mental health of children and young adults. (The current priority of Jonathan Haidt, co-chair of our new Advisory Council, of course).

But my delight turned to frustration—and honestly a bit of despair—as I dived into the piece. As so often, the fact that suicide, including teen suicide, is an overwhelmingly male problem was entirely ignored. In fact, the opposite impression was given. Here’s how Solomon describes the key statistics:

Between 2007 and 2021, the incidence of suicide among Americans between the ages of ten and twenty-four rose by sixty-two per cent. The Centers for Disease Control found that one in three teenage girls considered taking her life in 2021, up from one in five in 2011.

If you are reading my substack, there’s a good chance you already know that the suicide rate is much higher among boys and men than among girls and women. But imagine you don’t know that, and read that paragraph again. If you were then asked which gender was most at risk of suicide, you’d reasonably point to girls.

This impression would be confirmed if you read the whole essay in which Solomon describes the painful impact of five teen suicides, of which four are girls.

It’s essentially impossible to come away from this essay without a strong sense that the teen suicide crisis is, in fact, a teen girl suicide crisis. That is absolutely false. In fact, for every five teenagers dying from suicide, four are likely to be boys.

Any parent concluding that their daughter is at a much higher risk from suicide than their son has been badly misled. Not by some clueless blogger, but by one of the best-informed reporters on the subject of mental health, in his lead story in one of the most authoritative publications in the world.

I honestly don’t think it’s unfair to describe this as misinformation. It is certainly irresponsible.

Factlessness in the media

Solomon makes the same move as many reporters writing about suicide. He states the overall incidence of actual suicide, without a gender breakdown. He then reports on the share of teenagers who say they have considered suicide, this time highlighting the gender gap.

I am quite sure that the much-vaunted New Yorker fact checkers, with whom I’ve had the recent pleasure of working with, made sure Solomon’s numbers were correct. (They are). But nobody seems to have considered whether the facts were presented in an unbiased way.

But Solomon is not alone. This is becoming a self-perpetuating pattern. I’ll pick just one more example from many. A 2023 New York Times piece on adolescent mental health opened with the tragic case of the suicide of a 14 year-old girl, and then presented the key facts as follows:

According to new data released on Monday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly three in five teenage girls felt persistent sadness in 2021, double the rate of boys, and one in three girls seriously considered attempting suicide. The rates of sadness were the highest reported in a decade.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for adolescents and young adults in the United States.

Again, the reporters highlight the gender gap on the subjective measure (in this case feelings of persistent sadness), but do not provide a gender breakdown of the objective measure (death rates from suicide). So the impression is of a suicide problem that is bigger for adolescent girls than boys.

The facts

But that is not the case. Here is the trend in the absolute number of deaths from suicide in the 10-24 age range from 2007 to 2021:

The respective rises meant that there were 1,991 more deaths over the period for men, and 815 more deaths for women. And here’s the same chart but showing rates per 100,000:

Across the period as a whole, boys and young men have been about four times more likely than girls to lose their life to suicide, though the gap has narrowed somewhat, from almost a five-fold gap at in 2007 to a level closer to 3.5 since around 2015. Here’s the gender ratio:

It is perfectly appropriate to note that the rate of increase has been higher for women and girls than for boys and men, from a much lower base, and that as a result the gender gap has narrowed somewhat. But it is important to report both trends and levels, something that many reporters are failing to do.

It would be odd, for example, to report the much faster rate of wage growth for women than men in recent decades, but neglect to mention that men still earn more than women. It is in fact quite hard to imagine a responsible economics reporter doing that. But many health reporters are doing exactly the equivalent in their mental health coverage.

I’ll also note in passing that for the population as a whole, and over a longer time period, the gender gap in suicide has actually widened:

Going deeper: young men fueling the suicide crisis

If we dig a bit deeper into the trends, as we have over at AIBM, some important patterns emerge. (Big shout-out here to our research assistant Ravan Hawrami who has crunched all the numbers). I’ve written a lot about this, including in this newsletter, so I won’t go over all the same ground again.

But I do want to highlight one important trend, relevant to Solomon’s story, which is the recent increase in suicide among young men. Up to 2010, the rise in male suicide was being driven by men in middle age, as the green lines in the middle of the chart below show. But look at the orange bars on the left, showing that since 2010, the main story has been one of rising suicide rates among men aged 15 to 34:

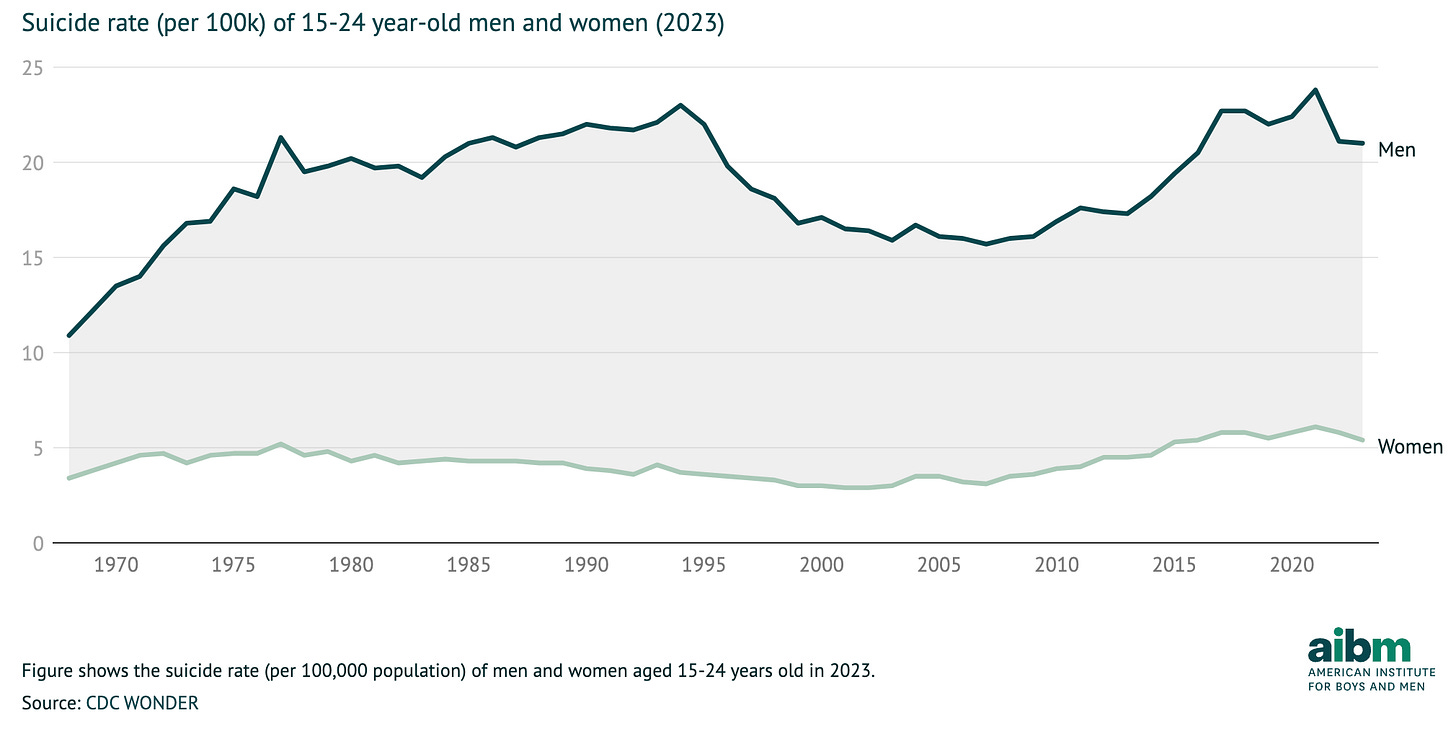

It’s important to note that rates have risen among young women too. Here are the trends for both men and women aged 15 to 24, for example:

In 2023, the rate for young men was 21; for young women, the rate was 5.

After conducting a similar analysis showing that suicide rates among men under 30 are now higher than other age groups, the psychologist Jean Twenge concluded that:

Suicide prevention efforts need to focus more on younger men than they do now.

She is right, of course. But it is hard to get policymakers to realize this when so many of our mainsteam media outlets don’t report the numbers in an even-handed way.

Time to face facts

On this issue I do sometimes feel like I’m banging the same drum over and over again. Occasionally, I feel like I might be banging my head against a brick wall.

To be fair to Solomon and his editors and fact-checkers, the CDC itself has yet to acknowledge the gender gap in suicide; it remains a glaring absence from the “Suicide Disparities” page. The unwillingness to simply show the strongly gendered nature of suicide risk has been institutionalized. (It’s striking that a New Yorker piece from Emily Greenhouse back in 2014 offered a much more balanced take).

It hardly need saying that the mental health challenges of girls and young women need to be treated with the utmost seriousness. The rise in self-reported rates of sadness and suicidal ideation Solomon refers to are a real cause for concern, as it is the potential role of social media.

But addressing the mental health challenges of women and girls does not require willful blindness to the worsening suicide crisis among young men. We can acknowledge and address both. But that’s only possible when the facts are stated accurately and clearly. We’ve really got to do better than this.

I wrote this in 2023 - https://www.washingtonpost.com/parenting/2023/04/14/teen-boys-suicide-mental-health/

Like you, I remain very frustrated by the fact that the CDC doesn't acknowledge this gender gap, particularly b/c they have very publicly highlighted increased rates of poor mental health & suicide attempts for girls without at all noting that the male rate is way above that. Or that their questions ask about "sadness" and "hopelessness" but not "rage" or "irritability" and may therefore be missing a lot of male depression and anxiety.

Well, if you want your piece published by the New Yorker, there are things you can't say.