Working class men: a troubling update

On many dimensions, men without a college degree are struggling. Like, really.

I am a near-obsessive about the need to bring both a class lens and a race lens to my work on boys and men. It’s just not possible to understand what’s really going on from inside the bubble of upper-middle class America. That’s why these were such strong themes in my book Of Boys and Men (recently seen on Barack Obama’s recommended reading list, thank you Mr President!).

But also why they guide the work of the American Institute for Boys and Men. To mark Labor Day, AIBM just published a data-rich report, “The State of Working Class Men”. There’s some deeply worrying trends in here. Even I was shocked by some of the findings, and I thought I knew this stuff pretty well.

I provide some some highlights—lowlights, really—here. But I’d urge you to look at the whole paper, and of course to share with others you think might find it useful.

As you’ll see, in some cases the class gap is much bigger than the gender gap, and vice versa. But overall the picture is clear. Working class men (those without 4-year college degrees) have been getting the sharp end of the stick on most fronts.

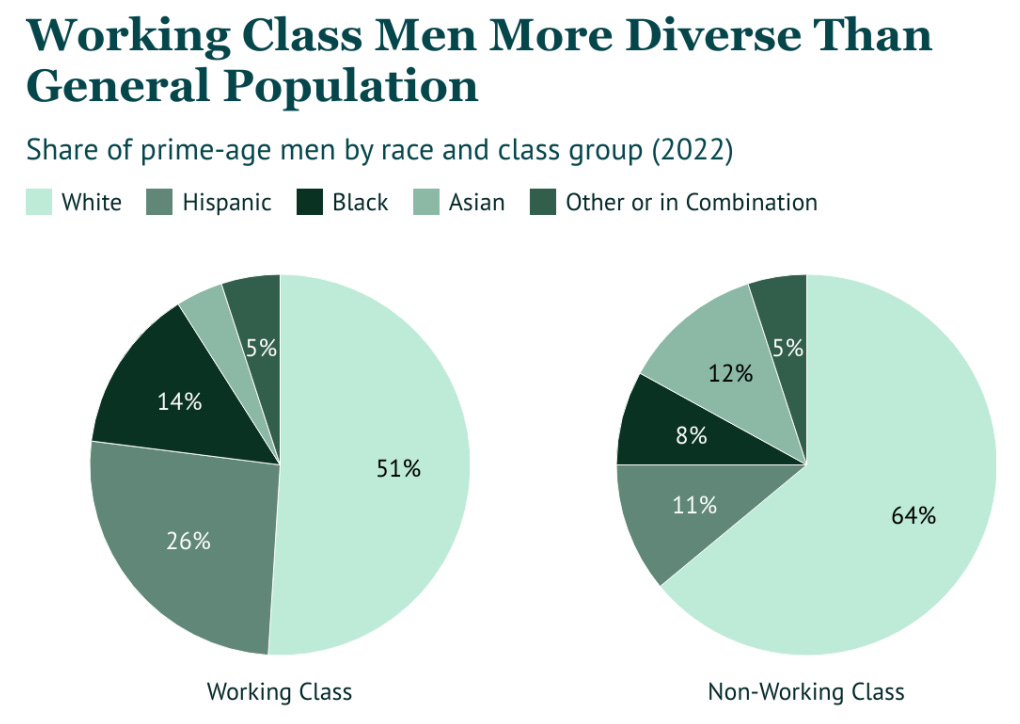

One thing I want to emphasize up front is the racial aspect of all this. Let’s be honest: the terms “working class” and “middle class” very often code as white. That’s unfortunate, because the working class is actually much more racially diverse than the non working class. In fact as our new report shows, white men account for only half of the male working class population:

So policies to help working class men as just as likely to help men of color as to help white men. It’s almost as if race, class and gender all matter, isn’t it? As Nick Hillman and Nicholas Robinson, UK education researchers, write:

Policy-making is not a zero-sum game in which you have to choose between caring about female disadvantage or the socio-economic gap or male underachievement. All three matter.

Working class men die more

Health is really on my mind right now. (See my Washington Post oped on this topic from last week if you missed it). I’ve written about here before too. I think if was writing Of Boys and Men now, I’d have a whole chapter on it. In our new report are some pretty striking findings.

Mortality rates are much higher for working class men at all ages. It really stunned me to realize that young working class men (aged 25 to 34) are more likely to die than middle-aged non-working class men (aged 45 to 54):

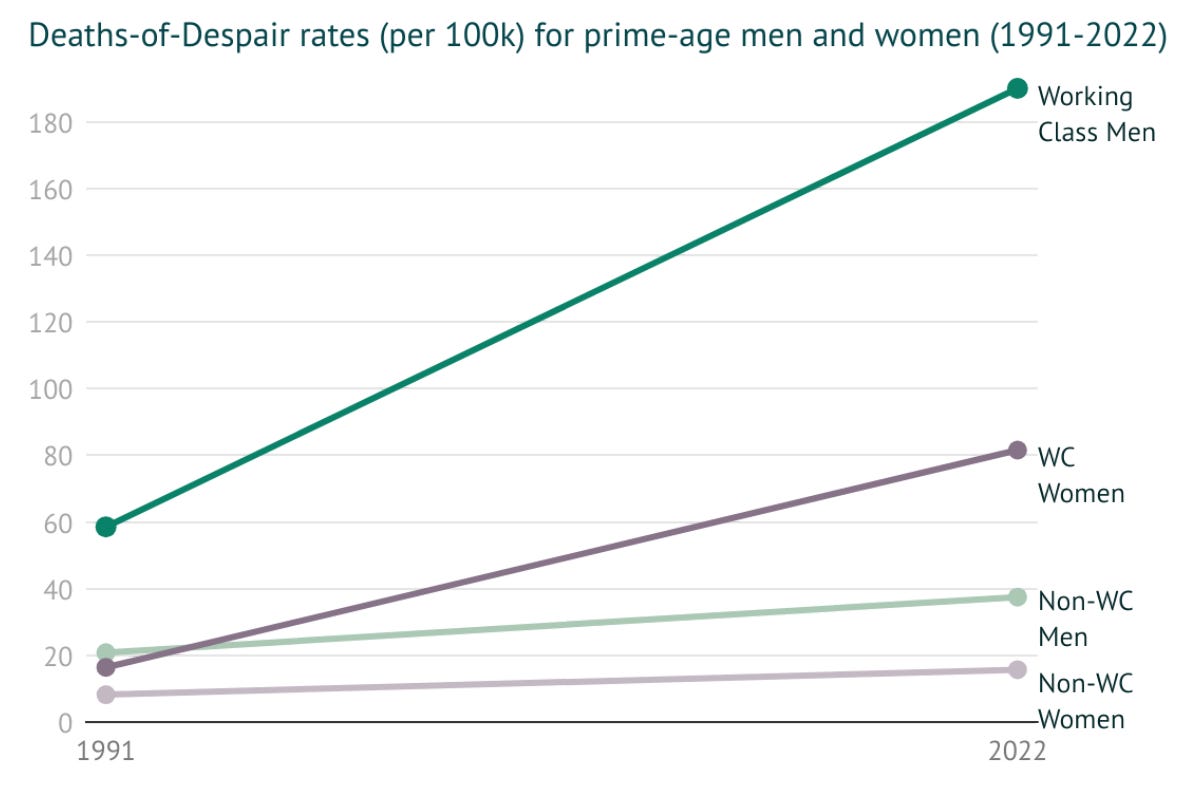

Why? For one thing, working class men face alarmingly high risks from “deaths of despair” such as suicide, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related deaths. I’m aware this term from Case and Deaton is falling out of favor, and for some good reasons. But I think it remains a useful shorthand. Rates have always been higher for working class men, but the gap has simply exploded in the last three decades:

It’s worth digging in a bit more, however. It turns out, perhaps not surprisingly, that drugs are the main story here. In 2022, the death rate from drug overdoses for working class men was nine times as high as for men with a Bachelor’s degree:

As we write in the report:

Deaths from alcohol-related causes and suicide are about three times as high among working class men as their non-working class counterparts. Notably, working class women are generally more vulnerable to deaths of despair than both men and women who are not working class. Suicide is the only cause of death where non-working class men are at more risk than working class women.

The health gap shows up as an employment gap. Working class men are in fact less likely to be working than non working class men. But in some ways even more telling is the difference in the reasons why they are not. Half of the working class men not in work (52%) say that this is because of illness or disability, compared to just 18% of non-working class men. Men with a college degree are most likely to be out of work because they are pursuing yet more education (24%):

Working class men are also more vulnerable to other health challenges, including workplace injuries and chronic diseases. Maybe it’s kind of obvious, but I was still blown away by the fact that workplaces deaths are basically a macabre monopoly of working class men:

Family and friends

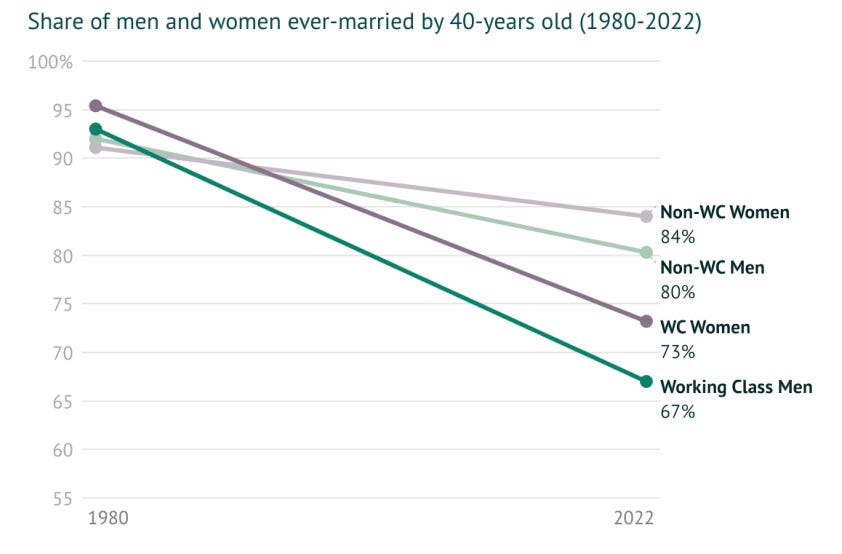

I wasn’t surprised by the growing class gap in marriage, because it was a theme of my work at Brookings. But I’m not sure it’s that well understood outside the wonkosphere, and I hadn’t really clocked the gender dimension before. Here’s the share who have ever been married by the age of 40:

Falls across the board, of course, but also a big class gap opening up. In 1980, which is not that long ago by my lights, fewer than one in ten working class men wouldn’t have tied the knot by 40. Now it’s one in three.

And the gap in living with children is perhaps even more consequential. The share of working class men with children at home has dropped from 67% in 1980 to 51% in 2022, a much lower share than for other groups, making them the least likely to live with children

As my friend Isabel Sawhill has written:

Family formation is a new fault line in the American class structure.

A world where only half of working class men are in a home with children is arguably a quite different to one where more than two-thirds are. The danger, as the scholar Shelly Lundberg writes, is that we have too many men who are “unburdened and unmoored”.

It doesn’t look like these men are filling the gap with friendships, either. Drawing on work from Daniel Cox and AEI (who kindly supplied a different data-cut), we show a large class gap in friendship:

Loneliness is a public health concern, as everyone now knows thank to the tireless work of the U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy. The two charts above suggest that it’s a general challenge, but especially for working class women and men. But note that working class women are the most likely to have children in their home.

Together, the story is that working class men are:

least likely to be married

and least likely to be living with children

and least likely to have a close friend

That this is not good is hardly a new insight. As Crooks says in John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men:

A guy needs somebody—to be near him. A guy goes nuts if he ain’t got nobody. I tell ya, a guy gets too lonely an’ he gets sick.

Class ceilings

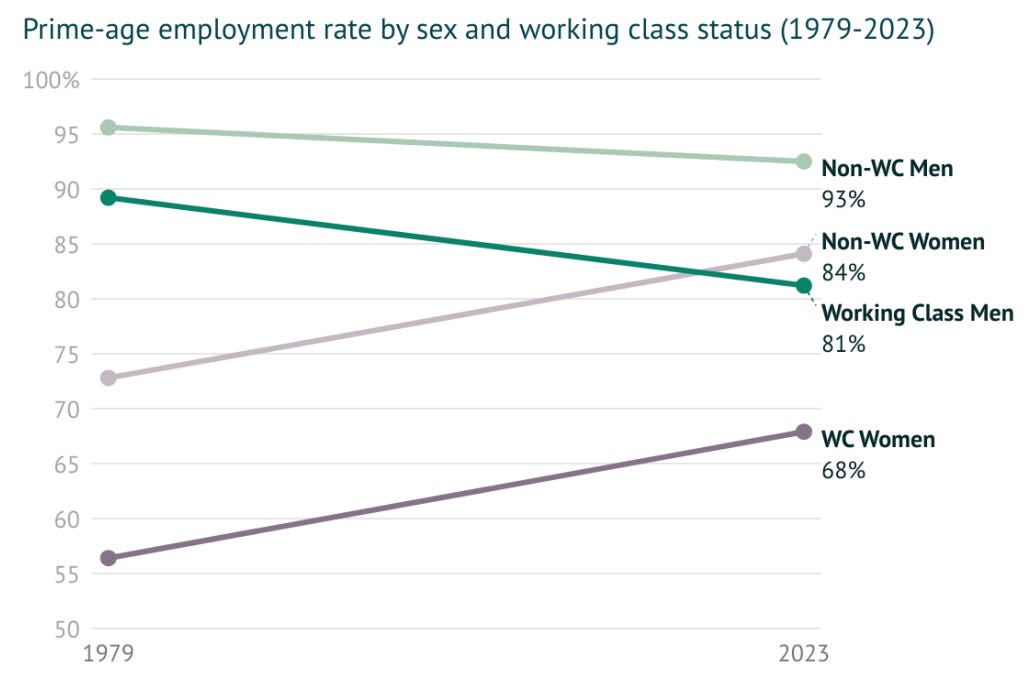

There is also plenty of material on the perhaps better-known challenges on the economic front, including the sharp decline in employment rates of working class men:

Added to which wages for working class men are basically the same today as they were in 1979:

Just because these facts might be reasonably well-known in wonkier circles, however, does not make them any less important. I actually think they underpin many of the other issues described in the paper.

Time to respond to the alarms

The dominant narrative of gender equality is framed almost exclusively in terms of the disadvantages of girls and women. But if we consider gender equality in the context of class, a different picture emerges. Especially at the bottom of the economic ladder, it is boys and men who are falling behind girls and women.

Any serious effort to improve rates of upward mobility or reduce economic inequality (perhaps to create an “opportunity economy”) must take into account the specific challenges being faced by boys and men. Otherwise, patterns of male disadvantage will repeat across generations. That will be bad for everyone, including women, and children, especially boys.

This will require more than a policy tweak here or a quick initiative there. These problems run deep and require a commensurate response. The good news is that the clear connection between economic inequality and the male malaise provides the possibility of bipartisan action. Conservatives worried about boys and men need to be concerned about economic inequality. But liberals worried about inequality must pay more attention to boys and men.

Thanks for pointing out these differences. However, the over-riding problem is the willingness of much of the culture to disdain a birth group by calling them toxic. This impacts all men whether they are working class or otherwise. Ignoring that is allowing the blatant hatred. Fix that first, and things will get better. Then get to the details.

Failing to pay attention to the needs and concerns of working class men is also having political consequences.

For better or worse, Donald Trump’s 2016 electoral victory and his flipping Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin Republican after 25 years of Democrat dominance came about because working class men saw him as someone who cared about their needs and concerns. (Did he really care? That’s another story for another time.)

Suffice it to say that right wing radicalization has made inroads among working class men because of the lack of concern for their needs by the center and left.