Gender gaps run both ways: the data

Metrics for gender equality should be what they say they are

I’ve a new research paper out at AIBM, “Beyond half measures: how to improve gender gap indices”. It’s something I’ve noodled with for years, and only been able to land with the analytical expertise of my co-author Allen Downey. It’s an empirical paper, but the basic underlying point of it is this: measures of gender gaps should measure gender gaps both ways, both when boys and men are at a disadvantage relative to girls and women, as well as vice versa.

That doesn’t mean there is no space for reports and metrics that only look at one side of the equation. You’d hardly expect me to oppose Movember’s “The Real Face of Men’s Health Report” for example; and I also appreciate KFF’s annual Women’s Health Survey. (By the way, I’ve not yet hit my $1,000 target on my Movember page, so if you’re feeling generous please do help me out…)

AIBM’s whole mission is after all about identifying areas where we can do better in helping boys and men to flourish, and how to do so. We produce plenty of reports focused on boys and men, and support others to do so too. Ditto, from the female standpoint, the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Independent Women’s Forum, National Partnership for Women & Families, National Women’s Law Center etc. This is all great: there is a real need to look at the experiences and challenges of women and men through a singular gendered lens.

A one-sided scale from WEF

But a measure of the overall gender gaps in a society should, in our view, be symmetrical. Unfortunately that is not the case for the most-cited international measure, the Global Gender Gap Report (GGGR) from the World Economic Forum. The Report is a huge data collection feat, and we want to acknowledge the work done by its authors.

The problem, as we point out in the paper, is that for most indicators, the GGGR scores in a range between zero (complete inequality) and 1 (complete equality), but truncates the scores at 1. In other words, gaps where women are behind men are counted, but gaps where men are behind women are not.

For the GGGR authors, this one-sidedness is a feature of the approach, not a bug. As they explain, two different approaches were considered in the report’s original design:

One was a negative-positive scale capturing the size and direction of the gender gap. This scale penalizes either men’s advantage over women or women’s advantage over men and gives the highest points to absolute equality. The second choice was a one-sided scale that measures how close women are to reaching parity with men but does not reward or penalize countries for having a gender gap in the other direction.

The GGGR opts for the second, “one-sided” scale, which means that:

The ratios obtained above are truncated at the “equality benchmark” […] considered to be 1, meaning equal numbers of women and men. [Truncation] assigns the same score to a country that has reached parity between women and men and one where women have surpassed men.

The report explains that this choice “determines whether the index is rewarding women’s empowerment or gender equality” and concludes that the one-sided scale is “more appropriate for our purposes.” The GGGR is thus explicitly designed to measure women’s empowerment and not gender gaps.

So a nation would be considered to have achieved “gender equality” even if men were hugely disadvantaged compared to women, so long as there were no domains in which women lagged behind men.

This wouldn’t matter if there were in fact no metrics where the gender gaps put boys and men behind girls and women. But there are plenty of such gaps, especially in terms of education and health and particularly in advanced economies.

A big gender gap in education

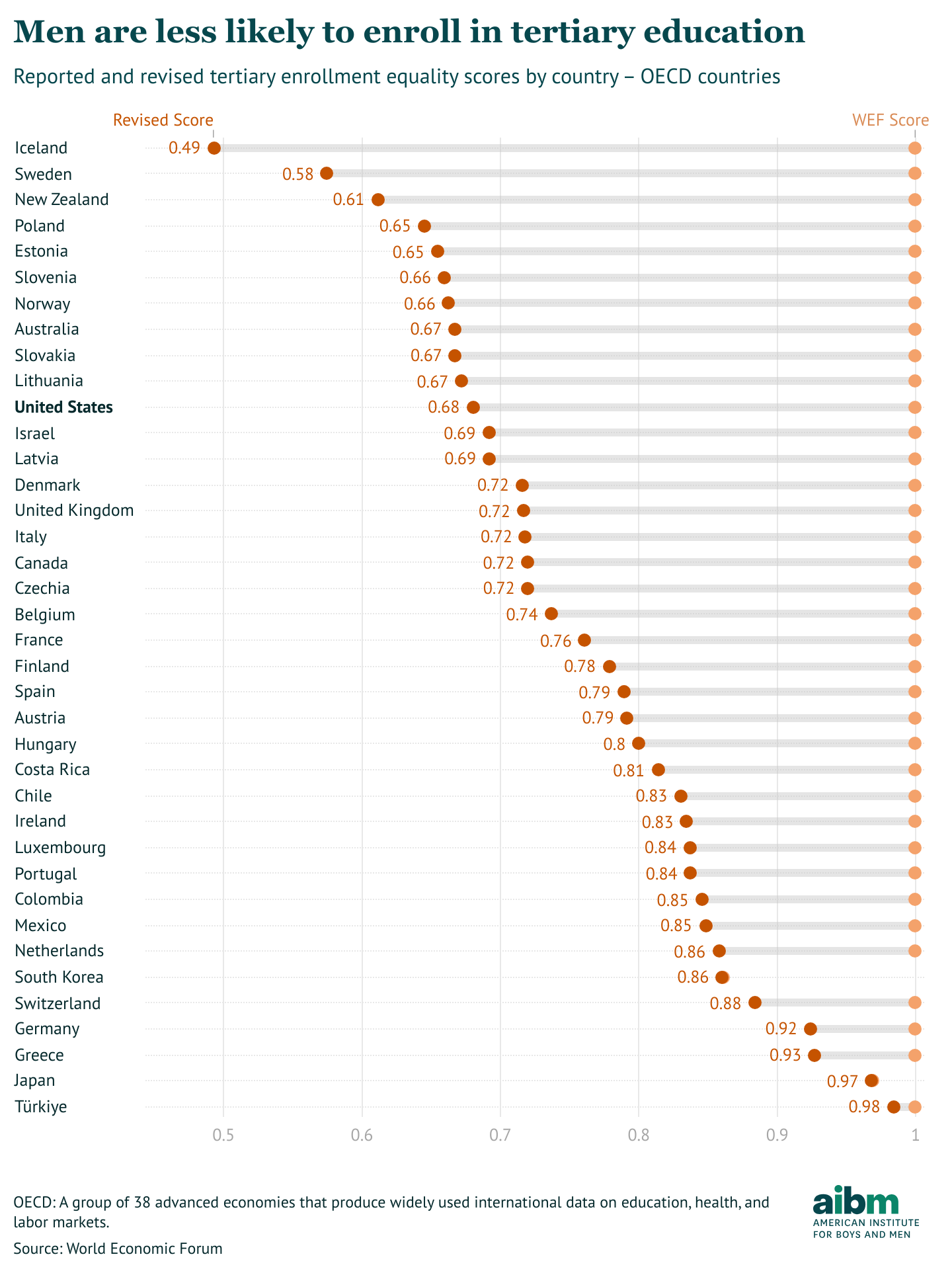

We recalculate the GGGR without truncation for the 38 member countries of the OECD; in other words, we include the gaps that run the other way. One of the biggest impacts in is education. We show that in 35 of 38 OECD countries there are more women than men enrolled in tertiary education, for example, often by a wide margin. Remember that the GGGR ranks all of these countries as gender-equal on this measure (i.e. with a score of 1). But as we show, the truth is rather different:

As the chart shows, Iceland, ranked by the GGGR as the most gender-equal country in the world, has the biggest gender gap in tertiary education enrollment, with twice as many women as men attending college. This gender gap is in fact the wider than any others in Iceland.

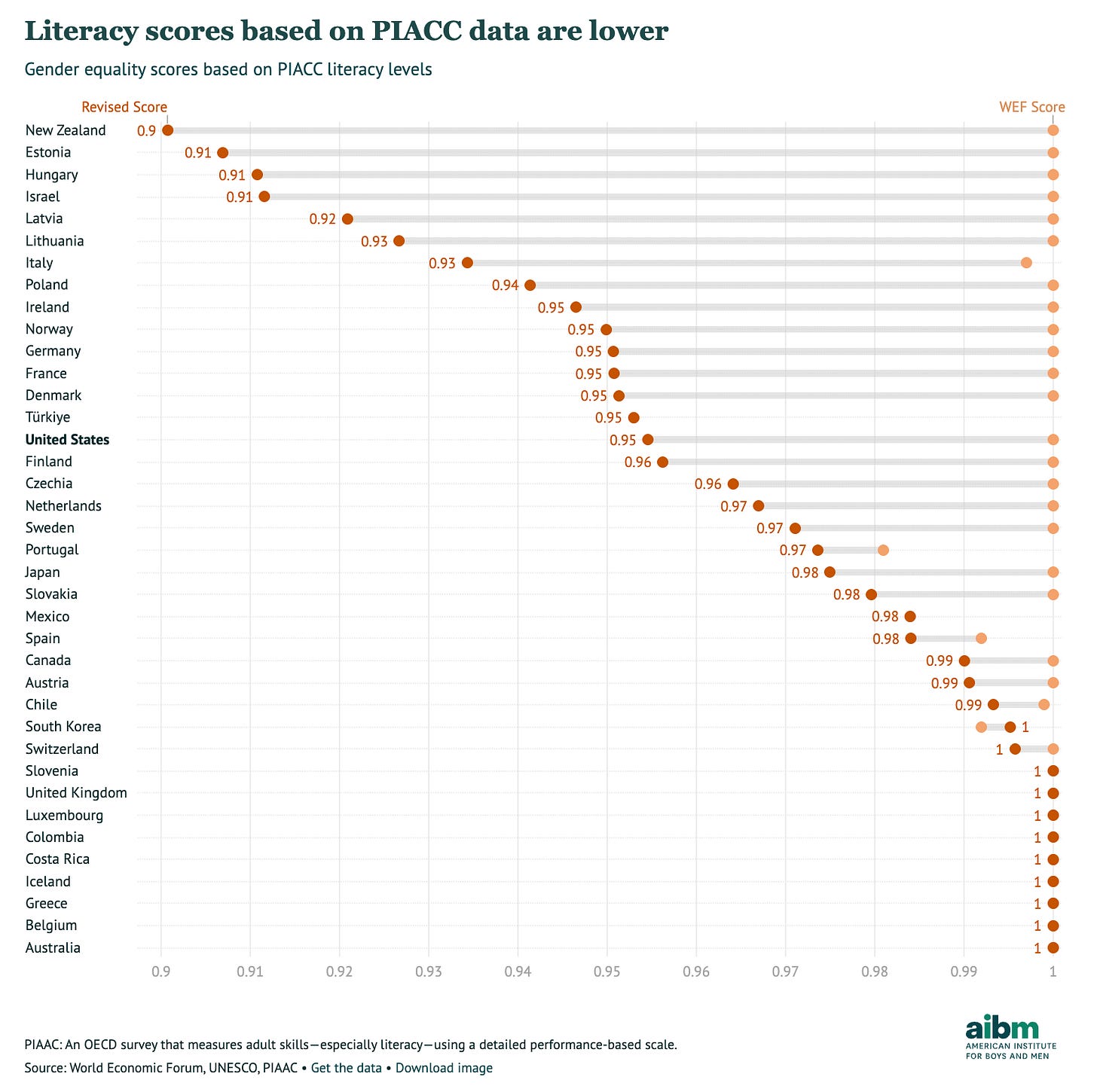

The GGGR also measures gender gaps in literacy, but uses a very low threshold in order to pick up disparities in less-advanced economies. In fact, there’s no attempt to measure gender gaps in literacy in OECD countries. From the perspective of the GGGR authors, this doesn’t really matter, because if there’s gender gap in literacy it is certain to be one where boys are behind girls - and they are not interested in gaps in that direction. The GGGR just assumes parity in literacy in very OECD country.

Allen and I instead use a higher level of literacy to examine gender gaps (though still low enough that 75% of adults across OECD countries surpass it). We find gender gaps almost everywhere, though not as big as for tertiary education:

Big, varied gender gap in life expectancy

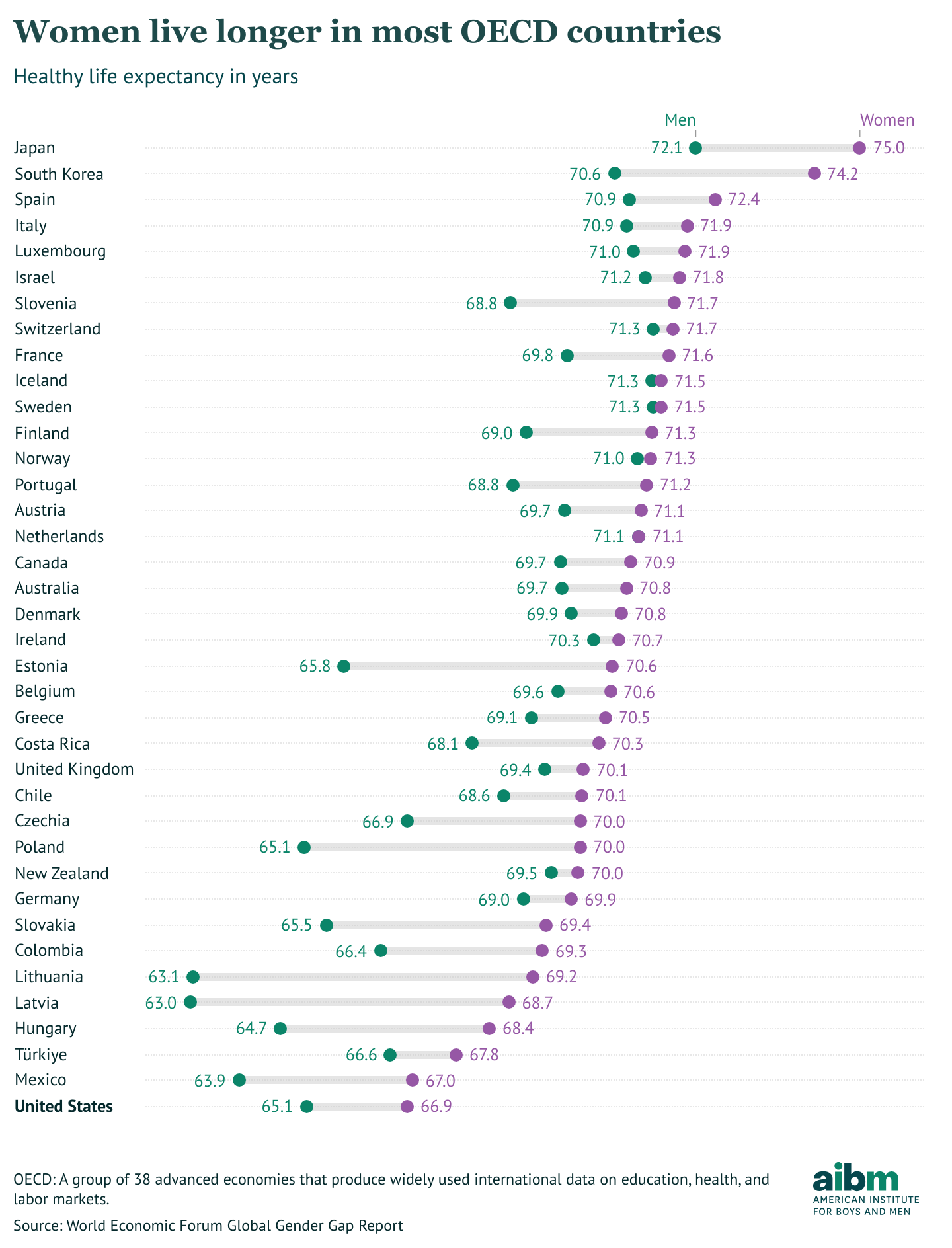

The GGGR also considers gender gaps in healthy life expectancy. Here the problem is not only that gender gaps disfavoring men are discounted, but that a certain gender gap is assumed to be natural. As the GGGR report explains:

[I]n the case of healthy life expectancy the equality benchmark is set at 1.06 to capture the fact that women tend to naturally live longer than men. As such, parity is considered as achieved if, on average, women live five years longer than men.

This means that a country where men die only four years before women is considered to be unequal - to women. This is a problem, given that there is absolutely nothing natural about a five year difference in healthy life expectancy. A century ago, the life expectancy gap was just two years in the U.S., but has tripled since.

We don’t need to look back in time to make this point, we can just look around the world. The data collected for the GGGR itself shows that yes, women live longer in most countries, but that there is also massive variation:

There are tiny gender gaps in the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Iceland for example, but very big gaps in many eastern and central European nations. We were surprised by the extent of variation on this measure, and we’ll likely be doing more work on the front. One thing is for sure, though. Such variation shows that it is inappropriate to arbitrarily assume that a five-year gap should be treated as normative for the purposes of measuring gender gaps.

In our paper, we remove this assumption and simply measure the gap. After all, whatever the cause of the gap, having fewer healthy years of life seems like a gender disparity worth considering.

There’s much more in our paper, including recalculated scores across a range of domains. It’s also worth saying that there are other weaknesses, to our minds, in the GGGR methodology, including a very weak survey question on gender pay gaps and an odd weighting system: is the number of years a country has had a female head of state really much more important that the share of women in parliament, for example? But we don’t touch any of these methodological decisions in our recalculations.

Let’s get better gender gap reports

There have been various attempts to produce alternatives to the GGGR. The Basic Index of Gender Inequality (BIGI) from Stoet and Geary looks at simple gender ratios in three domains: educational opportunities, healthy life expectancy and life satisfaction. This introduces useful new information, but by excluding economic gender gaps misses a big part of the picture, especially in terms of the ways women are worse off than men. We conclude our paper thus:

There is also a case for gender gap reports and indices that provide a more comprehensive overview of areas where men are behind women, as well as those where women are behind men. This would help policymakers who are concerned to address gender inequalities in both directions. We have made a partial attempt at such an approach here by revising the GGGR methodology, but there is scope for a much more robust approach.

I’d be excited to see the creation of a gender gap report that was genuinely even-handed, robust, credible and useful. This is an area crying out both for some higher-quality social science and a symmetrical approach.

What a relief to see this at last! I'm four-square in favor of gender equality and have worked on that front for years. But it has become increasingly clear that most of the energy has come from researchers (mostly women) who are just not all that interested in the struggles of men, and have failed to notice (or feel!) what is happening to men as the culture increasingly shifts in ways that redound to women's favor, often leaving men behind. Tragically, we are now seeing the cost of that--of men who have little sense of honorable and fulfilling male ways of being or contributing to society. Your emphasis on HEAL professions is enormously valuable in that regard. And perhaps with good data to back us up, we can begin to redress a few of the counter-inequities.

Feminists will do EVERYTHING and ANYTHING in their power to ensure that ANY data or information that shows that men are disadvantaged will NOT BE ALLOWED TO REACH the public.

Feminism is not about equality

It is an ideology based on nothing but hatred of men and boys and is really all about power and SPECIAL STATUS FOR WOMEN IN ALL THINGS

Feminism is the largest hate movement the world has ever seen

They hate 1/2 of world’s entire population