The underreported rise in male suicide

Boys and men are four times more likely to take their own lives but you could be forgiven for not knowing that

I’ve been out and about talking about my book a lot in recent months. (See my latest podcast appearance on Ezra Klein’s show, for example). One of the facts I cite a lot is that boys and men are at a four times higher risk of suicide. I’ve been surprised by how surprised people are by it. Of course, not everyone is studying boys and men. But that’s such a stark divide that it seems like it should be pretty well known. But it’s not, even among quite well-informed folks.

A Yale professor told me he didn’t know about the gender gap in suicide rates, just after he’d spoken on an panel on youth mental health and suicide. A CNN reporter got the numbers the wrong way round before I corrected them. A state legislator had to do a google search to confirm the truth of what I was saying.

This lack of awareness matters. The rise in suicide rates is a huge public health challenge. Understanding who is most at risk is important, not just for policymakers, but also for parents, educators and friends. For all of us.

The biggest risk factor for suicide: being male

Suicide rates are much higher among boys and men than among women and girls, at all ages, as CDC mortality data shows. Suicide among children before high school age is mercifully low, but rises after adolescence. Overall rates have been rising over the last couple of decades. Here are the rates for 1999 and 2019 for three selected age groups (this is on p. 63, Of Boys and Men):

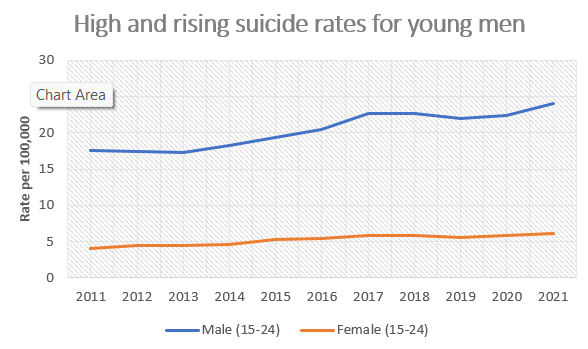

The rates have risen since 2019, especially for boys and men. In September 2022, the CDC released provisional suicide estimates for 2021. They show an increase over 2020:

The gender gap got wider, because the increase in suicide rates from 2020 to 2021 was bigger for men (4%) than for women (2%). As the CDC report, released in September 2022, put it:

For males, the age-adjusted suicide rate increased 3% from 2020 (22.0 per 100,000) to 2021 (22.7) Rates for males in age groups 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, and 65–74 increased significantly, with the largest percentage increase (8%) for those aged 15–24.

The story was a more encouraging one for girls and women, with no statistically significant rise in suicide rates for any age group. From the CDC summary again:

For females, the age-adjusted suicide rate in 2021 (5.6) was 2% higher than in 2020 (5.5), although the change was not significant. Rates increased for females in age groups 10–14, 15–24, 25–34, and 55–64, although none of these changes were statistically significant.

The most arresting change in suicide rates was among boys and young men aged 15 to 24. Among this group, the suicide rate in 2021 was 22.1, up by 8% from 2020:

This is one of the biggest year-on-year increases for any group in recent decades. Of course, 2021 was an exceptional year because of the pandemic, so it may be that the rate will come down again. It’s hard to know what caused the spike, so it is inevitably difficult to know if the upward trend in male suicide will continue.

But the overall picture is very clear: male suicide rates are high and rising.

(Note: even though the 2021 figures are provisional, they rarely change much if as all. As the CDC authors write: “[T]his analysis is based on more than 99% of expected death record. . . the findings in this report for provisional 2021 suicide data are expected to be consistent with final 2021 data.”)

Not enough attention to male suicide

I’ll be honest. I’d missed the growing gender disparity in the suicide figures in 2021. And that’s, like, my job. So I looked back at the media coverage of the release in September 2022. That exercise made me feel better, and then worse. It made me feel better as a scholar, because there was surprisingly little media coverage of the report. I could be half-forgiven for having missed it.

But made me feel worse as a policy wonk and a citizen, since the numbers in that report were very striking, very troubling and very important to know about.

What coverage there was generally did not highlight the dramatic rise in the suicide rate for boys and young men. One honorable exception was the Washington Post’s Health 202 newsletter:

But there wasn’t very much media coverage. What coverage there was did not point out the fact that the rise in suicide was among boys and men. This is part of a pretty established pattern by now. It is not the fault of the folks I’ve been talking to that they are not aware of the huge gender gap in suicide rates. It just doesn’t get much attention.

The CDC needs to take a hard look at itself

On this issue at least, I’m going to partly blame the CDC. The way they present suicide trends and statistics seems almost designed to distract attention away from the biggest disparity of all. Here’s a story I told Ezra:

I was having an argument with a men’s rights activist the other day. And he said, look, they don’t care about male suicide. I said, what are you talking about? Of course, they — first of all, who’s they? And what do you mean? He said he means — I mean the C.D.C. I mean the White House. I mean the government. They don’t care about male suicide. I said, yes they do. Why do you say that? He sent me a link. And the link was to the C.D.C. page on suicide disparities. He said, where does it talk about men? And he’s right. It doesn’t. It talks about all kinds of other disparities — by race, LGBTQ, rural, urban, veteran, et cetera. But there isn’t a subsection on men. It doesn’t just straightforwardly address the fact that there’s a massive, massive gender gap in suicide.

Take a look at the way the CDC presents the data on suicide. Here’s a screenshot of the top of the page the guy I was arguing with pointed me to:

He’s right. There is simply no mention of boys or men.

Similarly, on the CDC page titled “Facts About Suicide” is the following paragraph:

Some groups have higher suicide rates than others. Suicide rates vary by race/ethnicity, age, and other factors, such as where someone lives. By race/ethnicity, the groups with the highest rates were non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and non-Hispanic White populations. Other Americans with higher than average rates of suicide are veterans, people who live in rural areas, and workers in certain industries and occupations like mining and construction. Young people who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual have higher rates of suicidal thoughts and behavior compared to their peers who identify as heterosexual.

Again no mention of the fact that boys and men are at a four times greater risk of suicide.

It is perfectly possible to consume a lot of the CDC material on suicide risks by demographic group and come away with no idea that being male is the biggest risk factor of all.

I made a narrow point to Ezra about the political damage this does, by making the people claiming that society doesn’t care about men sound a lot less crazy than they should. But the much bigger point is that simply in terms of public health, not knowing who is at greatest risk is dangerous. In that sense, I think the CDC is failing in its public duty.

Getting it right

The power of data to drive attention to real problems has been demonstrated in recent weeks with the media and institutional coverage of the worsening mental health of teen girls, following the release of a different CDC report, based on an biannual survey of high schoolers.

This showed a very big increase in rates of depression and anxiety among teens, especially girls, in 2021. You have likely seen some of the reports. But the main findings were that most high school age girls (57%) reported that at some point in the last year (2021) they felt “so sad or hopeless almost every day for at least two weeks in a row that they stopped doing usual activities”. This was up from 47% in 2019, and was easily the biggest 2-year increase over the last decade. Here’s the CDC chart:

The CDC survey also found troublingly high numbers in 2021 in the share of girls who have “seriously considered attempting suicide” in 2021 (30%); “made a plan” for suicide (24%); attempted suicide (13%); and been injured in an suicide attempt (4%). These are high numbers and rising numbers, and are quite rightly setting alarm bells ringing. And in every case, the female share was twice as high as the male share.

When one in seven high school girls say they have tried to take their own life in the last year, we are clearly in the grip of what is being correctly described as a mental health crisis.

The hope is that more attention will be paid to the causes of the recent upsurge in mental health problems among girls and young women, not least the harms of social media. For an interpretation of the mental health trends for girls especially, I’d strongly recommend Jonathan Haidt’s new post on this topic, ”Why the Mental Health of Liberal Girls Sank First and Fastest”, and indeed his newsletter, After Babel, in general. Hell, just Jon’s work overall.

The silence on male suicide is damaging

Does it matter that the facts on male suicide are not strongly publicized by public health agencies, and therefore not well known even among many health professionals, educators and parents? As you might guess, I think it does.

The scholar in me thinks it’s important to base our conversations on any topic on the most solid ground possible, just in terms of basic facts. Neglecting what is easily the largest risk factor for suicide, i.e. being male, makes the whole discussion of suicide risk somewhat unmoored. Of course, it’s also important to look at other groups at risk, including the specific groups of boys and men who are at most risk, including men who live in rural areas, American Indian and Alaska Natives, LGBTQ men, and so on.

It is also very important that public policy is designed and resourced in line with where the risk factors are greatest. And for suicide, that means paying particular attention to boys and men. Among other things, that means increasing the take up of mental health services by men, who are currently 10 percentage points less likely than women to access mental health care (though the share has risen for both):

Why are men less likely to get mental health care? In part because they are less likely to say they have a mental health problem. But maybe in part because of a dearth of male therapists? (There’s a good post on this in Psychology Today by Jett Stone, “Why Is It So Hard to Find a Male Therapist?”).

Another reason could be a lack of health insurance, since men are at greater risk of being uninsured: 13.8% of men aged 19-64 in 2021 were uninsured, compared to 10.5% of women, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Better health insurance coverage is not only good for men suffering from mental illness, it’s good for all of us. A study by Elisa Jácome of Northwestern found that men with mental health problems who lose Medicaid coverage are 21% more likely to end up in prison. On this point, see this study, “Young Men Need More Medicaid” by Shawn Fremstad and his colleagues at CEPR, which shows that young men are much more likely to be without health insurance in states that did not expand Medicaid.

The broader point is that a lack of awareness of a social problem—in this case, high and rising male suicide rates—leads to a lack of attention not only from policymakers, but from society as a whole.

As always, taking seriously the mental health problems of boys and men does not mean taking any less seriously the mental health problems of girls and women. It is not a zero sum game. Or as Ezra put it, rather beautifully, in his introduction to our conversation:

At a meta level, I often think in politics you face this implicit sense that compassion or concern is zero sum, that to care about one group or one issue is to care less about another. I just don’t believe that. I actually think there’s evidence it is not true. Compassion is not measured out in teaspoons from a cup. It’s quite the opposite. I think it’s much more of a habit, something we get better at, something we have more capacity for, the more we practice it.

I’m currently working on a Masters degree in school counseling. We share classes with the BCBA and CMHC students as well as others entering the mental health field. I’ve encountered only two male students among my classmates so far and I can assure you that none of these future counselors and clinicians are being trained to meet the needs of the majority of their future students and clients. The struggles and needs of men and boys are never addressed. We have many, many lectures on how to address the needs of women and minority populations. While I think these discussions are valuable and should continue, some clear and intentional conversations about men and boys as well would also be valuable. As women entering an already female dominated field, wouldn’t we benefit from some instruction on how to meet the needs of the majority of our futures clients and students? When I’ve brought up these concerns, I’ve mostly been condescendingly dismissed. So not only is the suicide crisis among men growing, but the future of the profession meant to support them is not being adequately prepared.

I was telling a woman close to me (ok, it was my wife) about this article. She hadn’t heard that suicide rates were higher for men and boys, but she wasn’t surprised because ”men are more violent than women”. I let that pass because being married means learning to pick one’s battles, plus I like to give any idea the benefit of the doubt before I take issue with it. But it almost sounded like blaming the victim. I wonder how many people, men as well as women, believe similarly. Could this be a problem, too?